Georgism

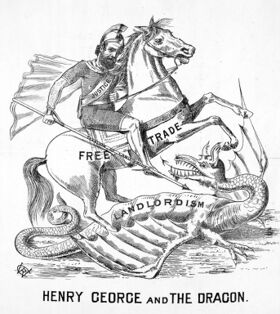

Georgism is the common name for the economic view which holds that the economic rent which landlords derive from land ownership—including from all natural resources, the commons, and urban locations—should be taxed directly for use by the state.

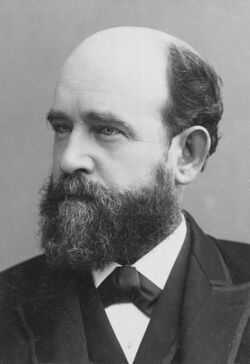

Liberal economic theory has tended throughout its history to oppose rent-seeking, particularly by landowners, as inefficient; this view is evident throughout the works of Adam Smith and other classical political economists. However, the name "Georgism" refers specifically to a view popularized by the work of American reformer Henry George (1839–1897) in the late 19th century, most notably in his 1879 work Progress and Poverty, holding that a single land-value tax would eliminate the main social ills of the late 19th century without a significant struggle against capital or the expropriation of any means of production, including land.

History

Henry George

George was born in 1839 into a middle-class family[citation needed] in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. Leaving school before his 14th birthday, George worked for two years as a clerk in an importing house and then went to sea, sailing to Australia and India. Back in Philadelphia in 1856, he learned typesetting, and in 1857 he signed up as a steward on a lighthouse tender bound for service on the Pacific coast. He quit the ship in San Francisco to join the gold rush in Canada but realized he had arrived too late and returned to California. He started working for newspapers and would take part in Democratic Party politics until 1880. In the process, he developed his writing and oratorical skills, but barely made a living doing odd printing jobs and attempting several newspaper enterprises.[1][2] He hit rock bottom with the birth of his second child:[2]

I stopped a man [on the street]—a stranger—and told him I wanted five dollars. He asked what I wanted it for. I told him that my wife was confined and that I had nothing to give her to eat. He gave me the money. If he had not, I think I was desperate enough to have killed him.[2]

After years of intermittent employment in the newspaper industry, including at the San Francisco Chronicle, a political connection secured him an appointment as state gas-meter inspector in 1876,[1] giving him the stability he needed to work on Progress and Poverty. The work caught the spirit of discontent that had arisen from the economic depression of 1873–78, achieving wide popularity in the burgeoning US labour movement and translations in several languages. George also produced pamphlets and magazine articles and lectured across the US and the UK to propagate his ideas.[1]

George moved to New York City in 1880 and became involved in politics there. In 1886, he ran for mayor representing the United Labor Party, a short-lived alliance of the Knights of Labor, the Socialist Labor Party, and over 100 other local organizations.[citation needed] George faced Democrat Abram Stevens Hewitt and Republican (and future president) Theodore Roosevelt in an election which was hotly contested, even provoking rivalry within the local Catholic church;[2] ultimately, however, when early vote counts favored George, the Republican political machine switched its support at the last minute to the Democratic Abram Stevens Hewett just in time to barely sink George at the expense of the young Roosevelt.[2] Roosevelt would temporarily leave politics after the crushing defeat.[2]

George appears to have held respect for the socialist and working class movements of Europe and expressed his condolences upon the death of Karl Marx in 1883:

I never had the good fortune to meet Karl Marx, nor have I been able to read his works, which are untranslated into English. I am consequently incompetent to speak with precision of his views. As I understand them, there are several important points on which I differ from them. But no difference of opinion can lessen the esteem which I feel for the man who so steadfastly, so patiently, and so self-sacrificingly labored for the freedom of the oppressed and the elevation of the downtrodden....

I honor Karl Marx because he saw and taught that the road to social regeneration lies not through destruction and anarchy, but through the promulgation of ideas and the education of the people. He realized that the enslavement of the masses is everywhere due to their ignorance, and realizing this, he set himself to work to master and to point out the social economic laws without the recognition of which all effort for social improvement is but a blind and fruitless struggle.

Karl Marx has gone, but the work he has done remains; whatever may have been in it of that error inseparable from all human endeavor will in turn be eliminated, but the good will perpetuate itself. And his memory will be cherished as one who saw and struggled for that reign of justice in which armies shall be disbanded and poverty shall be unknown and government shall become co-operation, that golden age of peace and plenty, the possibility of which is beginning even now to be recognized among the masses all over the civilized world.[3]

Within a few years, however, George evidently secured translations of Marx's works, bringing him into sharp conflict with the Marxist movement and Friedrich Engels himself:

Spread in the United States

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

Theory

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

Criticism

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

Quotes

Progress and Poverty

And while professors thus disagree, the ideas that there is a necessary conflict between capital and labor, that machinery is an evil, that competition must be restrained and interest abolished, that wealth may be created by the issue of money, that it is the duty of government to furnish capital or to furnish work, are rapidly making way among the great body of the people, who keenly feel a hurt and are sharply conscious of a wrong. Such ideas, which bring great masses of men, the repositories of ultimate political power, under the leadership of charlatans and demagogues, are fraught with danger....

— Henry George, Progress and Poverty, Introduction[4]

To raise wages in a particular occupation or occupations, which is all that any combination of workmen yet made has been equal to attempting, is manifestly a task the difficulty of which progressively increases. For the higher are wages of any particular kind raised above their normal level with other wages, the stronger are the tendencies to bring them back.... So that practically, ... that which trades’ unions, even when supporting each other, can do in the way of raising wages is comparatively little, and this little, moreover, is confined to their own sphere, and does not affect the lower stratum of unorganized laborers, whose condition most needs alleviation and ultimately determines that of all above them. The only way by which wages could be raised to any extent and with any permanence by this method would be by a general combination, such as was aimed at by the Internationals, which should include laborers of all kinds. But such a combination may be set down as practically impossible, for the difficulties of combination, great enough in the most highly paid and smallest trades, become greater and greater as we descend in the industrial scale.

Nor... must it be forgotten who are the real parties pitted against each other. It is not labor and capital. It is laborers on the one side and the owners of land on the other. If the contest were between labor and capital, it would be on much more equal terms. For the power of capital to stand out is only some little greater than that of labor. Capital not only ceases to earn anything when not used, but it goes to waste—for in nearly all its forms it can be maintained only by constant reproduction. But land will not starve like laborers or go to waste like capital—its owners can wait. They may be inconvenienced, it is true, but what is inconvenience to them, is destruction to capital and starvation to labor.— Progress and Poverty, Book VI: The Remedy. Ch. 1, Section III.[4]

See also

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Biography, Single Tax, & Progress and Poverty". Encyclopedia Britannica. 20 Jul 1998. Retrieved 30 Jan 2024.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Brookhiser, Richard (23 Mar 2023). "1886: The Men Who Would Be Mayor". City Journal. Retrieved 30 Jan 2024.

- ↑ Oatman, Bruce (25 Sep 2012). "Henry George's Letter at the Funeral of Karl Marx". georgistjournal.org. Retrieved 30 Jan 2024.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 George, Henry (23 Jan 2024). "Progress and Poverty, Volumes I and II: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 30 Jan 2024.