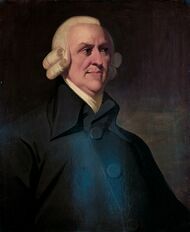

Adam Smith

| Political Economy |

|---|

| Authors |

| Concepts |

| Major works |

Adam Smith (June 5, 1723 — July 17, 1790) was a Scottish Enlightenment philosopher and political economist who is best known as the author of An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776).

Smith's economic theory reflected the historical conditions of the development of English and Scottish capitalism in the 18th century. Karl Marx characterized Smith as "a generalizing economist of the manufactural period"[citation needed]. The influence of this "manufactural period" was reflected in the fact that Smith attributed the decisive role in the development of productive forces to the manufactural division of labor, considering the manufactory as a typical form of enterprise. Smith acted as an ideologist of the bourgeoisie in the period when it played a progressive role. Vladimir Lenin characterized Smith as "a great ideologist of the advanced bourgeoisie" [citation needed]. Smith was not a conscious defender of the bourgeoisie [disputed ], but objectively, regardless of his subjective sympathies, he defended provisions corresponding to the requirements and interests of the development of the productive forces of capitalist society.

Quotes

The masters, being fewer in number, can combine much more easily; and the law, besides, authorizes, or at least does not prohibit their combinations, while it prohibits those of the workmen. We have no acts of parliament against combining to lower the price of work; but many against combining to raise it. In all such disputes the masters can hold out much longer. A landlord, a farmer, a master manufacturer, a merchant, though they did not employ a single workman, could generally live a year or two upon the stocks which they have already acquired. Many workmen could not subsist a week, few could subsist a month, and scarce any a year without employment. In the long run the workman may be as necessary to his master as his master is to him; but the necessity is not so immediate.

— The Wealth of Nations Book I, Ch. 8[1]

The interest of the dealers, however, in any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public.... The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.

— The Wealth of Nations Book I, Ch. 11, Part III[2]

Wherever there is great property there is great inequality. For one very rich man there must be at least five hundred poor, and the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of the many. The affluence of the rich excites the indignation of the poor, who are often both driven by want, and prompted by envy, to invade his possessions. It is only under the shelter of the civil magistrate that the owner of that valuable property, which is acquired by the labour of many years, or perhaps of many successive generations, can sleep a single night in security.... Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defence of the rich against the poor, or of those who have some property against those who have none at all.

— The Wealth of Nations Book V, Ch. 1, Part II[3]

The necessaries of life occasion the great expense of the poor. They find it difficult to get food, and the greater part of their little revenue is spent in getting it. The luxuries and vanities of life occasion the principal expense of the rich, and a magnificent house embellishes and sets off to the best advantage all the other luxuries and vanities which they possess. A tax upon house-rents, therefore, would in general fall heaviest upon the rich; and in this sort of inequality there would not, perhaps, be anything very unreasonable. It is not very unreasonable that the rich should contribute to the public expense, not only in proportion to their revenue, but something more than in that proportion.

— The Wealth of Nations Book V, Ch. 2, Part II, Article 1[4]

References

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/smith-adam/works/wealth-of-nations/book05/ch02b-1.htm

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/smith-adam/works/wealth-of-nations/book01/ch11c-3.htm

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/smith-adam/works/wealth-of-nations/book05/ch01b.htm

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/smith-adam/works/wealth-of-nations/book05/ch02b-1.htm

External links

- The Wealth of Nations at Marxists.org

- The Theory of Moral Sentiments at Marxists.org