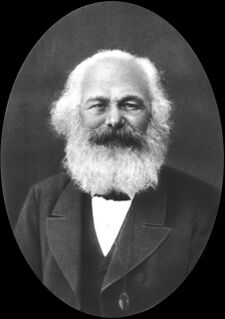

Karl Marx

Karl Marx FRSA[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Karl Heinrich Marx 5 May 1818 Trier, Prussia, German Confederation |

| Died |

14 March 1883 (aged 64) London, England

|

Buried | |

Residence | |

| Nationality | German, eventually stateless |

| Thesis | The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature |

| Occupation | Journalist, author, economist, revolutionary |

| Employer |

Newspapers:

|

| Political party | Various, including the IWMA |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 7, including Jenny, Laura and Eleanor |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

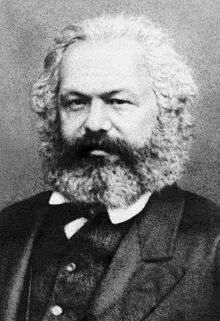

Karl Marx (May 5, 1818 - March 14, 1883) was a German political economist, revolutionary socialist, and philosopher. Today, Marx is considered one of the most influential figures in human history, due to his role in founding the Marxist school of thought, and as one of the three architects of modern social science, alongside Émile Durkheim and Max Weber.

Biography

Early life

Karl Heinreich Marx was born in Trier, Rhenish Prussia (present-day Germany), on May 5, 1818, the son of Heinrich Marx, a lawyer, and Henriette Presburg Marx, a semi-illiterate Dutchwoman, as one of 8 children (Henriette Marx, Eduard Marx, Mauritz David Marx, Hermann Marx, Emilie Conradi, Caroline Marx, and Louise Juta). Little else is known about his childhood other than the fact that he became the oldest son when his brother Mauritz died in 1819.

Both Heinrich and Henriette were descendants of a long line of rabbis. The Prussian authorities barred him from the practice of law because he was Jewish following an anti-Semitic law passed in 1815. Heinrich Marx converted to Lutheranism in about 1817. Yet he was largely irreligious, specifically choosing Lutheranism over Catholicism because he equated Protestantism with intellectual freedom,[2] and was also a passionate liberal activist, being an admirer of the works of Immanuel Kant and Voltaire. However, he was still fiercely patriotic and monarchistic, and educated his family as liberal Lutherans rather than atheists. Karl was baptized in the same church in 1824 at the age of six.

Education

Karl attended the Friedrich Wilhelm Gymnasium in Trier for five years, graduating in 1835 at the age of seventeen.[3] The gymnasium's program was the customary classical one—history, mathematics, literature, and languages, especially Greek and Latin. His father had chosen the school in particular because the school's principal was a friend of his, as well as a liberal, Kantian, and held in respect by the Rhenish people. Karl became very skilled in French and Latin, both of which he learned to read and write fluently. In later years he taught himself other languages, so that as a mature scholar he could also read Spanish, Italian, Dutch, Scandinavian, Russian, and English. As his articles in the New-York Daily Tribune show, he came to wield the English phraseology masterfully (he loved Shakespeare, whose works he knew by heart), although he never lost his strong German accent when speaking. The Prussian authorities grew suspicious of the school, in 1832, the school was raided. However, the school remained in operation, and Marx was able to graduate in 1835.

In October 1835, seventeen-year-old Marx enrolled in Bonn University in Bonn, Germany, where he attended courses primarily in law, as it was his father's desire that he become a lawyer. Marx, however, was more interested in philosophy and literature than in law.[4] He wanted to be a poet and dramatist. In his student days he wrote a great deal of poetry—most of it preserved—such as "The Fiddler," "Nocturnal Love," and "Transformation,"[5] many written to express his affection for Jenny von Westphalen, his childhood sweetheart whom he became engaged to in 1836. Her father, Baron Johann Ludwig von Westphalen, had introduced Marx to philosophy and the politics of Saint-Simon, a French utopian socialist. He spent a year at Bonn, studying little but partying and drinking a lot. He also piled up heavy debts. Marx's dismayed father took him out of Bonn and had him enter the University of Berlin, then a center of intellectual debate, where he studied Hegel. While Marx admired Hegel and Feuerbach's philosophy due to their belief in historical inevitability, he questioned what he saw as their philosophy's abstract and Idealist thought, as he believed that reality lies more in material economic conditions. In Berlin a coterie of brilliant thinkers was challenging existing institutions and ideas, including faith, philosophy, ethics, and politics.[6] He spent more than four years in Berlin, completing his studies with a doctoral degree in March 1841, having written a thesis entitled The Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature,[7] in which he compared the atomist philosophy of Democritus and Epicurus regarding contingency (statement that is neither necessarily undeniably true or undeniably false). However, he had to submit this dissertation to the University of Jena, as it would not be well received in Berlin, where he had a reputation as a Young Hegelian Radical.

Early intellectual development

Liberal agitation

At the age of 24, Marx decided to turn to journalism to make a living, and in 1842 he became the editor of the radical-democratic newspaper in Cologne, the Rheinische Zeitung ("Rhenish Gazette"), which was financed by wealthy liberals from the Rhineland. It ran for less than a year, only from October 1842 to the spring of 1843, at which point it was censored by the government, yet in it he published a very important article On Freedom of the Press. In it, he not only criticizes the Prussian government's censorship, but also the role of the press in society, as well as the relation between journalists and those who finance the press. He concludes that not only is the Prussian rationale behind censorship illogical, supposing that "to fight freedom of the press, one must maintain the thesis of the permanent immaturity of the human race... If the immaturity of the human race is the mystical ground for opposing freedom of the press, then certainly censorship is a most reasonable means of hindering the human race from coming of age," but also even the traditional liberal demand for a free press must go beyond simply defending newspapers from censorship by the state, but also beyond the control of newspapers and the means of communication for private interest.[8]

Socialist agitation

In Cologne he also met Moses Hess, a radical who organized socialist meetings, and whom Marx would associate with in the future. Hess, however, was one of the German "true socialists," a group whose philosophy Marx would later criticize for their failure to adequately explain the social conditions of communism.[9] Nonetheless, Hess would play a critical part in Marx's intellectual development, with him himself becoming a Marxist in 1847,[clarification needed] as it was at his socialist meetings that Marx would first learn the struggles of the German working class. Marx would first learn of the struggle of the Mosel wine farmers, who at first benefited from Prussian rule after Prussia gained the territories it had occupied in the Napoleonic Wars west of the Rhine river following the Vienna Peace Congress in 1815, since they could export their wine to Prussia tax free. However this ended with the establishment of the German Customs Union, or Zollverein, giving Prussian wine merchants an advantage over their competitors west of the Rhine. A bad harvest coupled with Prussia's unfavorable tax policy led to the many wine farmers in Mosel being reduced to poverty. Accounts of their suffering appalled Marx, who condemned the Prussian government in a newspaper article published in 1843 in the Rheinische Zeitung.[10] Following this, the Zeitung was banned, and Prussian authorities threatened to arrest Marx. Marx quickly married Jenny Von Westphalen, despite the objections of both families, and fled to Paris.

Laying the groundwork of Marxism

Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher

While in Paris, Marx started a newspaper titled the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, or Franco-German Annals.[11] It only ran for one issue, published in February 1844, ending due to the difficulty of evading censorship while distributing it from Germany to France, as well as from a disagreement between Marx and his friend and fellow Young Hegelian, Arnold Ruge. but it marked a turning point in Marx's lifetime, as while editing it, he met his lifelong companion and fellow Marxist Friedrich Engels. He also met the Russian Anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, whom he would butt heads with in the future over the issue of state power in the transition to socialism.

The issue would contain some of Marx's most critical works, including "On the Jewish Question", "A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right," as well as Engels' "Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy." Other contributors to the newspaper included his old mentor from Berlin, Bruno Bauer.

Embrace of communism

While in Paris, Marx declared himself a Communist (he chose the term "communist" so as to distinguish himself from the still popular Utopian socialist movement) and studied political economy and the French Revolution. There he wrote his Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts,[12] which were not discovered until the 1930s. In 1845, he was expelled from France by conservative statesman François Guizot, and fled to Brussels (Belgium was a country with more liberal laws on the press) with Engels. There, they made occasional trips to England to visit Engels' family, who owned cotton mills in Manchester. While in Brussels, Marx published a polemic against Pierre Joseph Proudhon's idealistic socialist text The Philosophy of Poverty,[13] in the Poverty of Philosophy.[14] It was also here that he worked on the Materialist Conception of History in the manuscript published after his death as The German Ideology.[15] It was also in Brussels that Marx joined the communist league, where he an Engels where commissioned in 1847 to write a manifesto for the league. This they did in 1848, and the resulting Communist Manifesto became one of their most famous works. After the panic caused by the outbreak of revolution in Europe, Marx was expelled from Brussels, and invited by the French provisional government to return to Paris. Soon after, he moved to Cologne to contribute to the revolutionary events in Germany, in particular as editor of the influential Neue Rheinische Zeitung (New Rhenish Gazette; 1848–9). He was summarily expelled from Cologne in 1849, moved again to Paris, and would face his final expulsion there, moving to London, where he would live for the rest of his life.

Journalism and study

Marx was still confident of further revolutionary action in Europe and rejoined the Communist League. He wrote two pamphlets on the 1848 revolution in France and its effects, titled the Class Struggles in France[16] and The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.[17] In the early 1850s, his family of himself, his wife, and four children fell into poverty, living in a three-room flat in Soho, London. They would have two more children, but only three of their six survived. They survived on monetary gifts from Engels, whose own income came from his family's cotton mill in Manchester, and a small amount of money Marx received from articles he wrote as European correspondent for the New-York Daily Tribune.

The International Workingmen's Association

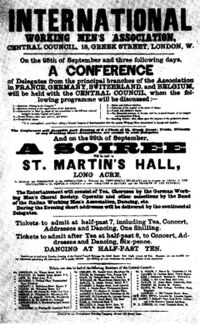

In 1864, Marx, Engels, and a group of various European radicals founded the International Workingmen's Association (IWMA), known today as the First International.

Capital Vol. I and growth of Marx's influence

Marx spent

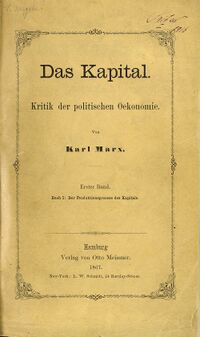

In 1867, the work was published under the title first volume of Capital: A Critique of Political Economy,[18] his largest and most significant work on political economy. He would spend the rest of his life working on the second and third volumes (which would be published by Friedrich Engels after Marx's death), and took a 3-year break from Capital to write Theories of Surplus Value,[19] a work detailing the various theories of political economy, particularly those of Adam Smith and David Ricardo. By 1871, his 17-year-old daughter, Eleanor Marx, was helping Marx with his work, and the deep understanding of capitalism that she gained from this would result in her playing in important role in the British labor movement.

Later years and death

In the last ten years of his life, Marx's health rapidly declined, and he could no longer work at the pace he could previously. Yet he still paid attention to the politics of his time, particularly concerning Russia and Germany. In the Critique of the Gotha Programme,[20] Marx criticizes his followers Karl Liebknecht and August Bebel for their compromises with state socialism in order to bring about a unified socialist party, and outlines the Dictatorship of the Proletariat stage of socialist development. He also wrote letters to Russian Menshevik Vera Zasulich in which he suggested the possibility of an early realization of socialism in Russia if the peasants reformed their economy on the basis of common ownership of land on the basis of the village[21] (this has often been used as justification by Leninists for the Russian Revolution of 1917). In 1881, Marx and his wife became ill, with Marx suffering but surviving from a swollen liver, but Jenny died later that year. In January 1883, his eldest daughter died from bladder cancer, casting Marx into a deep depression, and on March 14, 1883, Marx was found passed away in his armchair. His last words, having become a sad, broken old man by this point, were roared to his servant as "Go on, get out! Last words are for fools who have not said enough!" He was subsequently buried at High gate cemetery in London, where the Communist Party of Great Britain commissioned a new monument in his honor featuring a giant bust of himself, engraved with a line from the Communist Manifesto, "Workers of all lands unite!" and thesis eleven from his Theses on Feuerbach:[22] "Philosophers have interpreted the world in various ways, the point however, is to change it."

Thought

Intellectual development

Louis Althusser's idea of the "epistemological break", or separation, between the thought of the younger and older Marx has been debated.

Political positions

Marx's political positions on contemporary events shifted throughout the course of his life, but they are generally instructive of his actual positions and serve as examples for modern Marxists.

Incomplete list of works

Biographies

- Franz Mehring, Karl Marx: The Story of His Life at the Marxists Internet Archive.

- Otto Rühle, Karl Marx: His Life and Works at the Marxists Internet Archive.

- Vladimir Lenin, Karl Marx: A Brief Biographical Sketch With an Exposition of Marxism at the Marxists Internet Archive.

- Maximilien Rubel, Marx Life and Works

See also

References

- ↑ Marx became a Fellow of the highly prestigious Royal Society of Arts, London, in 1862.

- ↑ http://www.biography.com/people/karl-marx-9401219#synopsis

- ↑ http://biography.yourdictionary.com/karl-marx

- ↑ http://www.notablebiographies.com/Ma-Mo/Marx-Karl.html

- ↑ http://homepages.which.net/~panic.brixtonpoetry/marxpoetry.pdf

- ↑ http://atheism.about.com/od/philosophyofreligion/a/marx_2.htm

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1841/dr-theses/

- ↑ http://socialistreview.org.uk/376/marx-freedom-press

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/hook/1934/12/hess-marx.htm

- ↑ http://themanfrommoselriver.com/2007/09/26/karl-marx-and-mosel-wine/

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/df-jahrbucher/

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/manuscripts/preface.htm

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/economics/proudhon/philosophy/

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/poverty-philosophy/

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/german-ideology/

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/Class_Struggles_in_France.pdf

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1852/18th-brumaire/

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1863/theories-surplus-value/

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/gotha/index.htm

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1881/zasulich/

- ↑ https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/theses/theses.htm