Marxism–Leninism–Maoism

Marxism–Leninism–Maoism (MLM), often referred to as simply Maoism,[citation needed] is a communist ideology that views the ideological contributions of Mao Zedong and the Chinese Revolution as having advanced Marxism–Leninism to its greatest extent and revealed its limitations. Thus, Maoists generally view the later people's wars in Peru (1980–2000s), India (1967–present), Turkey (1973–present), Afghanistan (1978–1990s), and the Philippines (1969–present) alongside the Revolutionary Internationalist Movement as having then synthesized and universalized Maoism as a fundamental advancement from Marxism–Leninism.[1] It differs from Mao Zedong Thought (the present ideology of the Communist Party of China[2]) in its international scope, view of the Cultural Revolution as fundamentally correct, and in their continuing belief in the necessity for armed struggle. Taking inspiration from Mao's opposition to the Soviet Union following the rise to power of Khrushchev, Maoists almost universally subscribe to anti-revisionist positions.

History

Development (1948–2012)

Soviet-Yugoslav Split and Prelude to "The Great Debate"

In the later half of the 20th century, the International Communist Movement (ICM) was hit by shock after shock that began reigniting old debates and uncovering new issues that must be faced. The Chinese Revolution, which seized state power in 1949, was a shot across the bow of Euro-American imperialism and over the next decades revolution after revolution seized more and more territory. However, cracks were starting to show in the Movement. In 1943 the Communist International (or Comintern, 3rd International), the international body to which all communist parties were coordinated under democratic centralism, was disbanded under the pressure of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) and the USSR's national interests.[3] In the absence of central coordination and international discussion, ideology amongst the various parties began to drift, sparking fierce polemical debates. In the United States Earl Browder and the Central Committee of the CPUSA nearly liquidated the party entirely, and abandoned major lines and practices from the Comintern period, even ceding the CIO to what was once its mortal enemy in the labor movement: the American Federation of Labor (AFL).[4] Many parties such as the Japanese Communist Party abandoned the vanguard party model (in part or in full) in favor of mass party organizing.[5]

In 1948 Yugoslavia under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito and the Communist Party of Yugoslavia reoriented themselves away from the rest of the ICM and sought out aid from the United States to rebuild after World War II, introducing capitalist market reforms under the concept of "market socialism". This began a series of debates that would eventually blossom into "The Great Debate"[6] marked by polemical exchanges between the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (alongside other parties which remained Soviet-aligned) and the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (renamed to the League of Communists of Yugoslavia), and then later between the Soviet Party and the Chinese/Albanian parties, over core questions of Marxism–Leninism: what is a socialist economy and how does one transition to one? Is armed struggle necessary? What of democratic centralism? etc. These exchanges eventually led to a souring of relations (almost outright war[7]) between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union and an increasingly personal feud between their respective leaders: Tito and Joseph Stalin.[citation needed]

The Communist Party of China (CPC), as a force of rapidly increasing international importance in the Communist Movement, also actively took part in the international debate. Though they agreed with the Yugoslav assertion that armed struggle was necessary, they largely sided with the Soviet Union in the overall debate. At the time, the newly-founded People's Republic of China was collaborating closely with the Soviet party and government, and the two enjoyed close fraternal relations. Their relations hadn't always been perfect, Stalin and the CPSU had given the Chinese party disastrous advice at several points during its revolutionary struggle,[8][dubious ] but the success of the protracted people's war and need to rebuild meant these differences needed to be set aside for the time being. It wasn't until 1956, three years after the death of Stalin, that these questions would come back to the fore as part of The Great Debate.

The 20th Party Congress of the CPSU and Sino-Soviet Split

At the 20th Party Congress of the CPSU, Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin and many aspects of the CPSU's line during his leadership in his "secret speech".[9] This denunciation and the subsequent period of "de-Stalinization" in the Soviet Union stunned the International Communist Movement, and the positions of the Soviet party radically shifted during this time. A few months later, the Central Committee of the CPC published a response to the speech in their official publication (People's Daily) entitled "On the Historical Experience of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat." In it, the Chinese party praises the CPSU for what it saw at the time as combating a "cult of personality" and serious self-criticism:

"For more than a month now, reactionaries throughout the world have been crowing happily over self-criticism by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union with regard to this cult of the individual. They say: Fine! The Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the first to establish a socialist order, made appalling mistakes, and, what is more, it was Stalin himself, that widely renowned and honored leader, who made them! The reactionaries think they have got hold of something with which to discredit the communist parties of the Soviet Union and other countries. But they will get nothing for all their pains. Has any leading Marxist ever written that we could never commit mistakes or that it is absolutely impossible for a given Communist to commit mistakes? Isn’t it precisely because we Marxist–Leninists deny the existence of a “demigod” who never makes big or small mistakes that we Communists use criticism and self-criticism in our inner-party life? Moreover, how could it be conceivable that a socialist state, which was the first in the world to put the dictatorship of the proletariat into practice, which did not have the benefit of any precedent, should make no mistakes of one kind or another?"[10]

The CPC goes on to use the opportunity to analyze some of Stalin's supposed errors from their perspective, put forward the Mass Line as a strategy to mitigate or prevent the "cult of the individual", outline some of their own struggles in navigating left and right errors, and (importantly) state their understanding that the class struggle continues within socialism. However, though they praise Khrushchev's criticism of Stalin, there was also a thinly-veiled word of caution directed at him:

"Some people consider that Stalin was wrong in everything; this is a grave misconception. Stalin was a great Marxist–Leninist, yet at the same time a Marxist-Leninist who committed several gross errors without realizing that they were errors. We should view Stalin from [a] historical standpoint, make a proper and all-round analysis to see where he was right and where he was wrong, and draw useful lessons therefrom. [...] Great achievements have been made, but there are still shortcomings and mistakes. Just as one achievement is followed by another, so one defect or mistake, once overcome, may be followed by another, which in turn must be overcome. However, the achievements always exceed the defects, the things which are right always outnumber those which are wrong, and the defects and mistakes are always overcome in the end."

Over the years this word of caution would begin to transform into increasingly pointed critiques, with the CPC making veiled critiques of the CPSU through its polemics against the Yugoslav party and "revisionists". The CPC viewed Khrushchev's "de-Stalinization", especially the de-collectivization of agriculture and the reorganization of industry into state-owned businesses, as essentially the "market socialism" that the CPSU had previously denounced. They urged that the socialist system constructed under Stalin, though imperfect, be maintained and built upon:

"Were Stalin’s mistakes due to the fact that the socialist economic and political system of the Soviet Union had become outmoded and no longer suited the needs of the development of the Soviet Union? Certainly not. Soviet socialist society is still young; it is not even 40 years old. The fact that the Soviet Union has made rapid progress economically proves that its economic system is, in the main, suited to the development of its productive forces; and that its political system is also, in the main, suited to the needs of its economic basis. Stalin’s mistakes did not originate in the socialist system; it therefore follows that it is not necessary to “correct” the socialist system in order to correct these mistakes."[11]

The CPSU did the same through criticisms of ultra-left "splitists" in the movement, a term which other parties aligned with them then openly attached to the CPC.[12][13] Tensions rose as the CPSU began to call for an end to all polemics between communist parties for the sake of unity,[14] a line which much of the CPC leadership viewed as a further error due to their success in applying their "unity, criticism, unity" formula to their mass organizing and internal development. From On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People:

"To elaborate, it means starting from the desire for unity, resolving contradictions through criticism or struggle and arriving at a new unity on a new basis. In our experience this is the correct method of resolving contradictions among the people."[15]

The CPC refused to end open polemical debate or criticism, especially on issues which all were in agreement were critical to the movement. In 1963 the CPC sent a letter to the CPSU entitled A Proposal Concerning the General Line of the International Communist Movement which they immediately also published in several languages in a book, also including the letters sent to them by the CPSU for context.[16] In their letter, the CPC explicitly states their disagreements with the CPSU line, their view that right-revisionism is the principal trend causing splits in the movement, and makes a number of proposals to correct that revisionism and establish stronger unity in the revolutionary movement:

"The following erroneous views should be repudiated on the question of the fundamental contradictions in the contemporary world:

a) the view which blots out the class content of the contradiction between the socialist and the imperialist camps and fails to see this contradiction as one between states under the dictatorship of the proletariat and states under the dictatorship of the monopoly capitalists

b) the view which recognizes only the contradiction between the socialist and the imperialist camps, while neglecting or underestimating the contradictions between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie in the capitalist world between the oppressed nations and imperialism, among the imperialist countries and among the monopoly capitalist groups, and the struggles to which these contradictions give rise;

c) the view which maintains with regard to the capitalist world that the contradiction between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie can be resolved without a proletarian revolution in each country and that the contradiction between the oppressed nations and imperialism can be resolved without revolution by the oppressed nations;

d) the view which denies that the development of the inherent contradictions in the contemporary capitalist world inevitably leads to a new situation in which the imperialist countries are locked in an intense struggle and asserts that the contradictions among the imperialist countries can be reconciled, or even eliminated, by "international agreements among the big monopolies"; and

e) the view which maintains that the contradiction between the two world systems of socialism and capitalism will automatically disappear in the course of "economic competition", that the other fundamental world contradictions will automatically do so with the disappearance of the contradiction between the two systems, and that a "world without wars", a new world of "all-round co-operation", will appear.

It is obvious that these erroneous views inevitably lead to erroneous and harmful policies and hence to setbacks and losses of one kind or another to the cause of the people and of socialism."

The Soviet response was to publish an open letter denouncing the Chinese party and holding them principally responsible for the divisions in the International Communist Movement.[17] By 1964 the Sino-Soviet split was firmly apparent, with communist parties around the world taking sides in the great debate between the two lines. China found major state support in Enver Hoxha and the Party of Labour of Albania (PLA), which had broken with the CPSU for similar reasons.[18] This line struggle was also apparent within the communist parties around the world, where an already nascent anti-revisionist struggle exploded into the fore. Many parties saw major re-orientations or splits during this time.[19][20][21] Major international support for the Chinese position arose in the Communist Party of New Zealand (the pro-Soviet faction splitting off to form the Socialist Unity Party), initially the newly-founded Communist Party of India (Marxist) (later from the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist)),[22] the Communist Party of Brazil (the pro-Soviet faction splitting to form the Brazilian Communist Party)[23], and the "hard-left" wing of the CPUSA (principally composed of Black and Puerto Rican former members organized as the "Provisional Organizing Committee to Reconstitute a Marxist-Leninist Communist Party in the United States") which had largely been ejected from the party after its reconstitution in 1958.[24]

The Communist Party of China was no exception to this two-line struggle, and also faced fierce internal power struggles between its left wing (which coalesced around the leadership of Chairman Mao Zedong) and its right wing (led primarily by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping).[25][26][27] The party's "Great Leap Forward" had been disastrous, both failing to develop productive forces as-hoped and failing to overturn the old undemocratic ways of agricultural production in the countryside[27] (though the Soviet-directed first five-year plan had also failed in the latter sense).[25] A lack of planning, lack of consciousness among the masses, de-prioritization of agriculture (a Soviet recommendation),[citation needed] and outstripping of productive forces led to a precipitous drop in production in nearly all sectors after a few years of rapid expansion in production. Steel production in 1960 sank to 8 million tons in 1960 after a previous peak of 18.7 million tons and continued to fall for the next two years. This led to a major question of which direction the Chinese party should take.

Cultural Revolution in the East and the New Communist Movement in the West

The right wing of the party favored Liu's view that developing technical work was the central task of the party, that the level of productive forces must be raised first and foremost before social inequalities (national or economic inequality, unequal development between cities and countryside, etc.), socialist reforms, and the masses political consciousness could be addressed. Liu acknowledged that this could produce and reinforce an elite educated strata of academics and bureaucrats within Chinese society, but stated that this inequality was a natural fact of life:[25]

"People are different and have different qualities. Some are clever and some are stupid, some are tall and some are short, some strong and some weak, some are men and some are women, men are born different. [...] There is a division of labor and differences in work and career. For instance, in an army there are the high-level commanders and the lower-level commanders. [...] Within the party, there are those who are the responsible persons and those who are not, those who are leaders and those who are led."[28]

In practice, Liu's line led to bureaucratization and top-down organization in Chinese industry. Workers were expected to rigidly follow rules produced by unelected bureaucrats who became notorious for creating new rules with no attention to applicability, managers were inundated with massive amounts of paperwork and meetings to attend. The equipment section of the Tsitshihar Locomotive and Carriage Works alone had to fill out 170 forms per month and send them to the planning section, who in turn met with a representative of the power section in a series of cadre meetings. These forms and meetings multiplied over dozens of sections meant that the management of this one workshop was needing to constantly track thousands of moving parts and variables, filling out the appropriate paperwork and attending the necessary meetings, with no time to actually work alongside the workers they managed. Many of these managers were themselves previously workers supported by their coworkers on the assembly line, and the alienation this line produced coupled with an inflexible, opaque organizational structure led to rising resentment among industrial workers.[29]

China's Reversal and Anti-Revisionism's Crisis

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

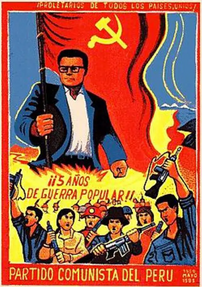

The Revolutionary Internationalist Movement

Marxism–Leninism–Maoism originated at the time of the formation of the Shining Path and its people's war in Peru. During the people's war, increased ideological coordination among Maoist parties culminated in the founding of the RIM (Revolutionary Internationalist Movement). Founding members of the Revolutionary Internationalist Movement included TKP/ML, the Communist Party of the Philippines, Iran's Sarbedaran, Communist Party Nepal (Maoist), India's Maoists, and the Revolutionary Communist Party (USA). All parties participating in the RIM adopted Marxism–Leninism–Maoism (MLM) as put forth by the Shining Path's leadership.

Modern histroy (2012–Present)

Though the RIM is now defunct, its constituent parties continue their struggles in their respective countries, and remain in general agreement on the need to regenerate unity and international cooperation in the movement.

Efforts to Reconstitute RIM

Present Line Struggle and the International Communist League

Tenets

Anti-Revisionism

Necessity of People's War

The Mass Line

Anti-Imperialism Through the Lens of Modern Neo-Colonialism

"Social-Imperialism" as a Returning Threat

Unity-Struggle-Unity and Two-Line Struggle

No "Peaceful Coexistence" with Capitalism

The "Party of a New Type"

Relation to Mao Zedong Thought

According to Mao, the peasant masses were to be the main force of the revolution, with the class-conscious proletariat acting as the leading force. The poor peasantry surrounding the cities would then wage a protracted war for democratic reform under the leadership of the Communist party. After the victory of the peasant army, it becomes the task of the party to carry out New Democratic revolution. Preserving the unity of the party with the masses is another concept central to the theories of the Chinese Revolution. Mao devised the strategy of the mass line to better coordinate party action with the masses. The two-line struggle was introduced to combat inequality arising from class struggle within socialism and to prevent a possible takeover of the party by hostile elements. Importantly, Mao also upheld the theory of Soviet social-imperialism. MLM thus maintains heavy (self-declared) anti-revisionist tendencies. MLM defers from Mao Zedong Thought in its belief in the universal (or near-universal) application of Mao's theory to material conditions outside of China.

See also

References

- ↑ Moufawad-Paul, J. (2021). Critique of maoist reason. Foreign languages press.

- ↑ "Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People's Republic of China". Wilson Center Digital Archive. 27 Jun 1981. Retrieved 20 Sep 2023.

These erroneous “Left” theses, upon which Comrade Mao Zedong based himself in initiating the "cultural revolution", were obviously inconsistent with the system of Mao Zedong Thought, which is the integration of the universal principles of Marxism-Leninism with the concrete practice of the Chinese revolution. These theses must be clearly distinguished from Mao Zedong Thought.

Translation from the Beijing Review 24, no. 27 (July 6, 1981): 10-39. - ↑ "Dissolution of the Communist International". marxists.org.

- ↑ Bay Area Study Group. (1979). The Roots of Browderism 1935-1945. In On the Roots of Revisionism: A political analysis of the international communist movement and the CPUSA, 1919-1945. essay, Revolutionary Road Publications.

- ↑ Kota (Host). (2021, May 4). The History of Marxism in Japan w/ Gavin Walker - Part 2 [Audio podcast episode]. In Against Japanism. https://againstjapanism.buzzsprout.com/1738110/8459145-the-history-of-marxism-in-japan-w-gavin-walker-part-2

- ↑ Communist Party of China. (2021). Documents of the Communist Party of China: The Great Debate (Vol. 1). Foreign languages press.

- ↑ Perović, Jeronim (2007). "The Tito–Stalin Split: A Reassessment in Light of New Evidence". Journal of Cold War Studies. MIT Press. 9 (2): 32–63. doi:10.5167/uzh-62735. ISSN 1520-3972.

- ↑ Snow, E. (1968). Red Star over China. Grove Press. "Invoking the prestige of the [Comintern] and the “expert” military knowledge of [Otto Braun] (who spoke no Chinese and voiced his views through Po Ku, as interpreter), Po Ku undermined the authority of both Chu Teh and Mao Tse-tung. [...] Mao was in 1934 also dropped from the all-powerful revolutionary military council [...] Mao was suspended from the PB and may have been put under surveillance by the newly organized security police (modeled after Stalin’s) headed by Teng Fa. [...] In those circumstances Chiang Kai-shek launched his well-prepared Fifth Extermination Campaign which ended in the defeat of the Red Army and the dissolution of Soviet Kiangsi."

- ↑ "Khrushchev's Secret Speech, 'On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences,' Delivered at the Twentieth Party Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union", February 25, 1956, Wilson Center Digital Archive, From the Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 84th Congress, 2nd Session (May 22, 1956-June 11, 1956), C11, Part 7 (June 4, 1956), pp. 9389-9403.

- ↑ Communist Party of China. (2021). On the Historical Experience of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. In Documents of the Communist Party of China: The Great Debate (Vol. 1, pp. 1–14). essay, Foreign languages press.

- ↑ Communist Party of China. (2021). More on the Historical Experience of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. In Documents of the Communist Party of China: The Great Debate (Vol. 1, pp. 15–45). essay, Foreign languages press.

- ↑ Workers of All Countries Unite, Oppose Our Common Enemy. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1962; pp. 1-21. The article originally appeared in Renmin Ribao on December 15, 1962.

- ↑ Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. (1963, March 8). A Comment On The Statement Of The CPUSA. Renmin Ribao.

- ↑ Communist Party of China. A Proposal Concerning the General Line of the International Communist Movement. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1963; pp. 108-115. "The open, ever aggravating polemics are shaking the unity of fraternal Parties, seriously damaging our common interests. The disputes which have arisen within the ranks of the international communist movement obstruct the successful struggle against imperialism, weaken the efforts of the socialist countries in the international arena, adversely affect the activities of fraternal Parties, especially of those in capitalist countries where a complicated internal political situation has arisen. [...] It was these considerations that guided the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the C.P.S.U. Comrade N. S. Khrushchov when speaking at the Sixth Congress of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany he proposed on behalf of our Party that polemics among Communist Parties be discontinued as well as criticism of other Parties within one's own Party. As known, this proposal found a wide response and support in the world communist movement."

- ↑ Mao, Z. (1966). Mao Tse-Tung: On the correct handling of contradictions among the people. Foreign Languages Press.

- ↑ A Proposal Concerning the General Line of the International Communist Movement. The Letter of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in Reply to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union of March 30, 1963. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1963

- ↑ The Polemic on the General Line of the International Communist Movement. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1965; pp. 526-86. The open letter was originally published in Russian in Pravda on July 14, 1963.

- ↑ Reflections on China, Vol. 1, page 7

- ↑ Philippine Communist Party-1930. (2018, January). A Short History Of The PARTIDO KOMUNISTA NG PILIPINAS (PKP-1930, the Philippine Communist Party). pkp-1930.com. http://www.pkp-1930.com/history

- ↑ Wilcox, V. G. (1963, December 27). The Leadership of the C.P.S.U. Has Taken the Revisionist Path. Peking Review.

- ↑ Haywood, H. (1977). For a revolutionary position on the negro question. Liberator Press.

- ↑ "Communist Party in Kerala". CPI(M). Archived from the original on 14 March 2012.

- ↑ "96 years of the Communist Party of Brazil – PCB". Redspark. 31 March 2018.

- ↑ Marxist-Leninist Vanguard, Vol. 1, No. 3, November 1958.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Cynthia Lai, Historic Lessons of China's Cultural Revolution, The 80’s, Vol. II, No. 3, n.d. [1981-2]

- ↑ Mobo, G. (2008). The Battle for China’s Past: Mao and the Cultural Revolution. Pluto Press.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Dongping, H. (2008). The Unknown Cultural Revolution: Life and change in a Chinese village. Monthly Review Press.

- ↑ Liu Shaoqi, “Democratic Spirit and Bureaucracy,” Collected Works, Vol. 1, p.81

- ↑ Stephen Andors, China’s Industrial Revolution–Politics, Planning and Management, 1949 to the Present, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977,) p. 190.