Reserve army of labour: Difference between revisions

(adding a cleaner intro to →Pre-capitalist parallels: that abstracts away from the specific historical instance cited, in case other examples are added later) |

m (→Pre-capitalist parallels: added a footnote regarding an antiquated word to the section) |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

=== Pre-capitalist parallels === | === Pre-capitalist parallels === | ||

Prior to the advent of the [[Capitalism|capitalist mode of production]], in areas of society where [[wage labour]] existed (i.e., outside of [[slavery]] and [[serfdom]]) there were many instances throughout history where a labour-power shortage caused a rise in wages, or a surplus of labour-power caused a reduction in wages. One of the most prominent examples of this: In 1348, the [[Black Death]] (a bubonic plague pandemic) struck [[England]], killing anywhere from 3 to 7 million people.<ref>[https://archive.org/details/plantagenetengla00pres_0 Prestwich, M.C. (2005). Plantagenet England: 1225–1360. Oxford: Oxford University Press.] ISBN 0-19-822844-9.</ref> It has been suggested that the plague, like some others in history, disproportionately affected the poorest people, who were already in generally worse physical condition than the wealthier citizens.<ref>[https://www.science.org/content/article/black-death-fatal-flu-past-pandemics-show-why-people-margins-suffer-most "From Black Death to fatal flu, past pandemics show why people on the margins suffer most"]. [https://web.archive.org/web/20211001204644/https://www.science.org/content/article/black-death-fatal-flu-past-pandemics-show-why-people-margins-suffer-most Archived] from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2023.</ref> Nevertheless, ''with such a large overall population decline from the pandemic, wages soared in response to a labour shortage''.<ref>Scheidel W (2017). The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. <nowiki>ISBN 978-0691165028</nowiki>, pages 292-293, page 304</ref> On the other hand, in the quarter century after the Black Death in England, it is clear many labourers, [[artisans]] and [[craftsmen]], those living from [[money]]-wages alone, did suffer a reduction in [[real income]]s owing to rampant [[inflation]].<ref>Munro J (2004). ''[https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/15748/1/MPRA_paper_15748.pdf "Before and After the Black Death: Money, Prices, and Wages in Fourteenth-Century England"]''. New Approaches to the History of Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe. The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters. page 352 [https://web.archive.org/web/20200115230318/https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/15748/1/MPRA_paper_15748.pdf Archived] from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.</ref> [[Landlord|Landowners]] were also pushed to substitute monetary [[rent]]s for labour services in an effort to keep tenants.<ref>[https://www.britannica.com/event/Black-Death "Black Death | Causes, Facts, and Consequences". Encyclopædia Britannica]. [https://web.archive.org/web/20190709135155/https://www.britannica.com/event/Black-Death Archived] from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.</ref> In 1349, [[Edward III of England|King Edward III]] made a failed attempt to freeze wages paid to labourers at their pre-plague levels. The ordinance is indicative of the labour shortage caused by the Black Death. It also shows the beginnings of the redefinition of societal roles:<ref>[https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/seth/ordinance-labourers.asp King Edward III, ''Ordinance of Labourers'' (1349)], [https://archive.li/zJBqN archived]</ref> <blockquote>Because '''a great part of the people, and especially of workmen and servants, late died of the pestilence''', many seeing the necessity of masters, and '''great scarcity of servants''', will not serve unless they may receive '''excessive wages''', and some rather willing to beg in idleness, than by labour to get their living; we, '''considering the grievous incommodities, which of the lack especially of ploughmen and such labourers may hereafter come''', have upon deliberation and treaty with the prelates and the [[nobles]], and learned men assisting us, of their mutual counsel ordained: | Prior to the advent of the [[Capitalism|capitalist mode of production]], in areas of society where [[wage labour]] existed (i.e., outside of [[slavery]] and [[serfdom]]) there were many instances throughout history where a labour-power shortage caused a rise in wages, or a surplus of labour-power caused a reduction in wages. One of the most prominent examples of this: In 1348, the [[Black Death]] (a bubonic plague pandemic) struck [[England]], killing anywhere from 3 to 7 million people.<ref>[https://archive.org/details/plantagenetengla00pres_0 Prestwich, M.C. (2005). Plantagenet England: 1225–1360. Oxford: Oxford University Press.] ISBN 0-19-822844-9.</ref> It has been suggested that the plague, like some others in history, disproportionately affected the poorest people, who were already in generally worse physical condition than the wealthier citizens.<ref>[https://www.science.org/content/article/black-death-fatal-flu-past-pandemics-show-why-people-margins-suffer-most "From Black Death to fatal flu, past pandemics show why people on the margins suffer most"]. [https://web.archive.org/web/20211001204644/https://www.science.org/content/article/black-death-fatal-flu-past-pandemics-show-why-people-margins-suffer-most Archived] from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2023.</ref> Nevertheless, ''with such a large overall population decline from the pandemic, wages soared in response to a labour shortage''.<ref>Scheidel W (2017). The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. <nowiki>ISBN 978-0691165028</nowiki>, pages 292-293, page 304</ref> On the other hand, in the quarter century after the Black Death in England, it is clear many labourers, [[artisans]] and [[craftsmen]], those living from [[money]]-wages alone, did suffer a reduction in [[real income]]s owing to rampant [[inflation]].<ref>Munro J (2004). ''[https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/15748/1/MPRA_paper_15748.pdf "Before and After the Black Death: Money, Prices, and Wages in Fourteenth-Century England"]''. New Approaches to the History of Late Medieval and Early Modern Europe. The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters. page 352 [https://web.archive.org/web/20200115230318/https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/15748/1/MPRA_paper_15748.pdf Archived] from the original on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.</ref> [[Landlord|Landowners]] were also pushed to substitute monetary [[rent]]s for labour services in an effort to keep tenants.<ref>[https://www.britannica.com/event/Black-Death "Black Death | Causes, Facts, and Consequences". Encyclopædia Britannica]. [https://web.archive.org/web/20190709135155/https://www.britannica.com/event/Black-Death Archived] from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.</ref> In 1349, [[Edward III of England|King Edward III]] made a failed attempt to freeze wages paid to labourers at their pre-plague levels. The ordinance is indicative of the labour shortage caused by the Black Death. It also shows the beginnings of the redefinition of societal roles:<ref>[https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/seth/ordinance-labourers.asp King Edward III, ''Ordinance of Labourers'' (1349)], [https://archive.li/zJBqN archived]</ref> <blockquote>Because '''a great part of the people, and especially of workmen and servants, late died of the pestilence''', many seeing the necessity of masters, and '''great scarcity of servants''', will not serve unless they may receive '''excessive wages''', and some rather willing to beg in idleness, than by labour to get their living; we, '''considering the grievous incommodities'''{{Efn|The word "incommodities" in this quote from King Edward III has a less of an economic definition than one might expect, given the context. It simply means "inconveniences" rather than having anything to do with commodities, or the lack thereof. Commodities accommodate needs (i.e. have use value), and therefore "commodity" and "accommodate" share the same etymology with the Latin word "commodus," meaning "proper, fit, appropriate, convenient, satisfactory." So the fact that King Edward is saying that the "inconveniences" i.e. the "incommodities" happen to be a lack of commodities is an amusing coincidence.}}''', which of the lack especially of ploughmen and such labourers may hereafter come''', have upon deliberation and treaty with the prelates and the [[nobles]], and learned men assisting us, of their mutual counsel ordained: | ||

That every man and woman of our realm of England, of what condition he be, free or bond, able in body, and within the age of threescore years, not living in merchandise, nor exercising any craft, nor having of his own whereof he may live, nor proper land, about whose tillage he may himself occupy, and not serving any other, if he in convenient service, his estate considered, be required to serve, he shall be bounden to serve him which so shall him require; and '''take only the wages, livery, meed, or salary, which were accustomed to be given in the places where he oweth to serve, the twentieth year of our reign of England''' [1347], '''or five or six other commone years next before'''.</blockquote>This [[Feudalism|feudal]] example shows how the a decrease in the supply of labour-power corresponds to an increase in the market price of labour-power. | That every man and woman of our realm of England, of what condition he be, free or bond, able in body, and within the age of threescore years, not living in merchandise, nor exercising any craft, nor having of his own whereof he may live, nor proper land, about whose tillage he may himself occupy, and not serving any other, if he in convenient service, his estate considered, be required to serve, he shall be bounden to serve him which so shall him require; and '''take only the wages, livery, meed, or salary, which were accustomed to be given in the places where he oweth to serve, the twentieth year of our reign of England''' [1347], '''or five or six other commone years next before'''.</blockquote>This [[Feudalism|feudal]] example shows how the a decrease in the supply of labour-power corresponds to an increase in the market price of labour-power. | ||

Revision as of 18:35, 22 October 2023

The reserve army of labour is a Marxist economic concept denoting a deliberate surplus in the supply of available labour-power created and maintained by the bourgeoisie in order to drive down the wages of the working class. According to this concept, the bourgeoisie exercise their political power to keep employment artificially lower than it would otherwise be, and maintain a large body of unemployed, underemployed or non-proletarianized people who can serve as scabs or strikebreakers in the event of labour unrest. Before the concept came into its own, bourgeois authors writing in the early 19th century mentioned lowering wages by increasing the labour supply.[1] The concept from the standpoint of labour activism was first described in a prototypical form by the Chartist James Bronterre O'Brien in the 1830s,[2] subsequently discussed by Friedrich Engels in The Condition of the Working Class in England,[3] then given its most familiar form by Marx in Capital: A Critique of Political Economy.[4] It was subsequently commented upon and expanded upon by many other socialist economists and political figures, including Vladimir Lenin.[5][6][7][8] Despite its origins with English Chartism, and its usage by bourgeois economists,[9][10] it is sometimes treated as a strictly Marxist hypothesis in academic literature.[11] Lenin said that the reserve army of labour are "the workers needed by capitalism for the potential expansion of enterprises, but who can never be regularly employed."[12]

Introduction

Definition

The Reserve army of labour consists of the chronically unemployed or underemployed surplus working class population whose existence benefits the capitalist class by driving down down wages (the market price, as opposed to natural price, of labour-power) and thereby driving up rates of profit. This surplus population is created by changes in the organic composition of capital and the tendency of the class-conscious bourgeoisie to act collectively in their own class interests. The reserve army of labour is also used for procuring scabs to use against labour strikes, further weakening the political and economic power of the organized workers.

Context

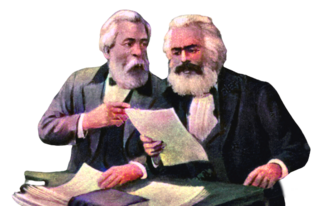

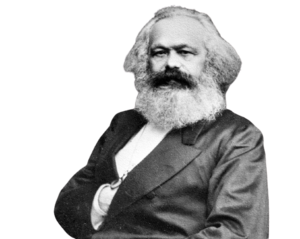

In Capital: Critique of Political Economy, Volume I, Chapter 25, Section 3, titled "Progressive Production of a Relative surplus population or Industrial Reserve Army",[4] Karl Marx develops the idea of a reserve army of labour, also sometimes called an industrial reserve army, a reserve army of unemployed, or relative surplus population. Marx, however, did not invent the term "reserve army of labour". It was already being used by Friedrich Engels in his 1845 book The Condition of the Working Class in England.[3] What Marx did was theorize the reserve army of labour as a necessary part of the capitalist organization of labour-power.

History and development of the idea of the reserve army of labour

Pre-capitalist parallels

Prior to the advent of the capitalist mode of production, in areas of society where wage labour existed (i.e., outside of slavery and serfdom) there were many instances throughout history where a labour-power shortage caused a rise in wages, or a surplus of labour-power caused a reduction in wages. One of the most prominent examples of this: In 1348, the Black Death (a bubonic plague pandemic) struck England, killing anywhere from 3 to 7 million people.[13] It has been suggested that the plague, like some others in history, disproportionately affected the poorest people, who were already in generally worse physical condition than the wealthier citizens.[14] Nevertheless, with such a large overall population decline from the pandemic, wages soared in response to a labour shortage.[15] On the other hand, in the quarter century after the Black Death in England, it is clear many labourers, artisans and craftsmen, those living from money-wages alone, did suffer a reduction in real incomes owing to rampant inflation.[16] Landowners were also pushed to substitute monetary rents for labour services in an effort to keep tenants.[17] In 1349, King Edward III made a failed attempt to freeze wages paid to labourers at their pre-plague levels. The ordinance is indicative of the labour shortage caused by the Black Death. It also shows the beginnings of the redefinition of societal roles:[18]

Because a great part of the people, and especially of workmen and servants, late died of the pestilence, many seeing the necessity of masters, and great scarcity of servants, will not serve unless they may receive excessive wages, and some rather willing to beg in idleness, than by labour to get their living; we, considering the grievous incommodities[a], which of the lack especially of ploughmen and such labourers may hereafter come, have upon deliberation and treaty with the prelates and the nobles, and learned men assisting us, of their mutual counsel ordained: That every man and woman of our realm of England, of what condition he be, free or bond, able in body, and within the age of threescore years, not living in merchandise, nor exercising any craft, nor having of his own whereof he may live, nor proper land, about whose tillage he may himself occupy, and not serving any other, if he in convenient service, his estate considered, be required to serve, he shall be bounden to serve him which so shall him require; and take only the wages, livery, meed, or salary, which were accustomed to be given in the places where he oweth to serve, the twentieth year of our reign of England [1347], or five or six other commone years next before.

This feudal example shows how the a decrease in the supply of labour-power corresponds to an increase in the market price of labour-power.

Pre-Marxist use, before 1845

Before the concept of the reserve army of labour was referred to directly from the standpoint of workers and pro-worker activists, it was referred to indirectly by the bourgeoisie from their perspective within the capitalist system. In an economic treatise from 1774, British Agriculturalist Arthur Young states:[19]

The national wealth increased the demand for labour, which had always the effect of raising the price; but this rise encouraged the production of the commodity, that is, of man or labour, call it which you will, and the consequent increase of the commodity sinks the price.

— Arthur Young, 1774

In the above, Arthur Young establishes the point, prerequisite to the concept of the reserve army of labour, that labour (or, for Marx, labour-power) is not only a commodity, but that its price (wages) decreases with an increase in the population (reserve army of labour) due to the resulting decrease in the demand for labour. Writing to member of Parliament Samuel Whitbread in 1807, Thomas Malthus advised:[1]

[. . .] if a more than usual supply of labour were encouraged by the premiums of small tenements,[b] nothing could prevent a great and general fall in its price. — Thomas Malthus, 1807

In the above, Malthus is speaking of labour itself (not yet distinguished from labour-power) as a commodity, and suggesting that it is subject to the principle of supply and demand, and that therefore an abundant supply of workers corresponds to a decrease in the cost of labour, since the workers will be forced to accept lower wages in the process of underbidding each other. In an 1815 article[20] published in the North American Review and Miscellaneous Journal, the following analysis is given which is a prototypical form of the Marxist idea of the reserve army of labour, from a bourgeois standpoint:

[. . .] if the advanced price of provisions is not [yet high enough] that the labourer can [nevertheless] support his family, [the labourer] will continue to suffer a gradual [decrease] of his wages, [until] a suspension in the [growth] of population causes the market to be understocked with labour; in which case a competition [between capitalists] for labour will restore in some degree the proportion between the price of provisions and labour. A contrary effect happens when a scarcity of labour raises its price beyond the just[c] level; this is obviously relieved by an increase of population, and the value of labour is sunk down to a corresponding balance with the value of provisions.[d][e]

According to Michael Denning, writing for the New Left Review, Issue #66, in December 2010, in an article titled "Wageless Life",[2] the concept of a reserve army of labour was used before Engels by the Chartist labour leader Bronterre O’Brien as early as 1839:

Radicals, particularly the Chartists and Fourierist associationists, imagined the new factory workers as great industrial armies, and this common trope led the Chartist leader [James] Bronterre O'Brien to write of a reserve army of labour in the Northern Star in 1839. The young Engels picked up that image in The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, and Marx would invoke the metaphor occasionally, distinguishing between the active and reserve armies of the working class. By the end of the nineteenth century, it was part of the commonsense understanding of unemployment: by 1911, even the Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of labour could conclude that, ‘however prosperous conditions may be, there is always a “reserve army” of the unemployed’ — Michael Denning, New Left Review, 2010, issue 66, article entitled "Wageless Life"[2]

First socialist use of the idea by Engels, 1845

In The Condition of the Working Class in England,[3] in the chapter titled "Competition," Engels introduces the idea of the "reserve army of workers" in the following passage:

[...]English manufacture must have, at all times save the brief periods of highest prosperity, an unemployed reserve army of workers, in order to be able to produce the masses of goods required by the market in the liveliest months. This reserve army is larger or smaller, according as the state of the market occasions the employment of a larger or smaller proportion of its members. And if at the moment of highest activity of the market the agricultural districts and the branches least affected by the general prosperity temporarily supply to manufacture a number of workers, these are a mere minority, and these too belong to the reserve army, with the single difference that the prosperity of the moment was required to reveal their connection with it. When they enter upon the more active branches of work, their former employers draw in somewhat, in order to feel the loss less, work longer hours, employ women and younger workers, and when the wanderers discharged at the beginning of the crisis return, they find their places filled and themselves superfluous – at least in the majority of cases. This reserve army, which embraces an immense multitude during the crisis and a large number during the period which may be regarded as the average between the highest prosperity and the crisis, is the “surplus population” of England, which keeps body and soul together by begging, stealing, street-sweeping, collecting manure, pushing hand-carts, driving donkeys, peddling, or performing occasional small jobs. In every great town a multitude of such people may be found. It is astonishing in what devices this “surplus population” takes refuge. — Friedrich Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England, 1845[3]

Summary

In the above passage, Engels gives the prototype of the idea, establishing:

- The reserve army of unemployed workers is sought after precisely because of their unemployment. This unemployment makes them available for the "liveliest" months of market activity, during which "greater masses of goods are required," (i.e. are more demanded by consumers) compared with the rest of the year. A modern example of this principle in action might be the type of a chronically unemployed person who gets a low-paying part-time job at a Halloween store, selling costumes during the month of October.

- These "liveliest months" of market activity constitute a form of economic crisis in miniature. Engels refers to the reserve army as "the wanderers discharged at the beginning of the crisis."

- The reserve army of workers includes not only the chronically unemployed, but the chronically under-employed, who belong to the "districts and the branches least affected by the general prosperity[...]", i.e. the internal colonies, those parts of a given geographical region which have a lower standard of living than their surroundings.

- when the chronically under-employed [men] return to their original jobs after being used as part of the reserve army of workers, they find their positions have been taken workers who, owing to their social position, are even more desperate and marginalized than themselves, usually women and children, in the historical context in which Engels was writing. This marginalizes the men further, and makes them part of a "surplus population."

- This "surplus population" often becomes part of the lumpenproletariat, or homeless, and must keep itself alive through crime, begging, and unpleasant odd jobs. This makes them more subject to death, disease, imprisonment, and exploitation above and beyond what is usual even for the average proletariat.

- This "surplus population" can be found "in every great town" of England, and by extension, every geographical region in which the capitalist mode of production prevails.

Development of the idea by Marx in Capital, 1867

The first mention of the reserve army of labour in Marx's writing occurs in a manuscript entitled "Wages",[21] which he wrote in 1847, but did not publish:

Big industry constantly requires a reserve army of unemployed workers for times of overproduction. The main purpose of the bourgeois in relation to the worker is, of course, to have the commodity labour[f] as cheaply as possible, which is only possible when the supply of this commodity is as large as possible in relation to the demand for it, i.e., when the overpopulation is the greatest. Overpopulation is therefore in the interest of the bourgeoisie, and it gives the workers good advice which it knows to be impossible to carry out. Since capital only increases when it employs workers, the increase of capital involves an increase of the proletariat, and, as we have seen, according to the nature of the relation of capital and labour, the increase of the proletariat must proceed relatively even faster. The above theory, however, which is also expressed as a law of nature, that population grows faster than the means of subsistence, is the more welcome to the bourgeois as it silences his conscience, makes hard-heartedness into a moral duty and the consequences of society into the consequences of nature, and finally gives him the opportunity to watch the destruction of the proletariat by starvation as calmly as any other natural event without bestirring himself, and, on the other hand, to regard the misery of the proletariat as its own fault and to punish it. To be sure, the proletarian can restrain his natural instinct by reason, and so, by moral supervision, halt the law of nature in its injurious course of development. — Karl Marx, Wages, 1847[21]

The idea of the labour force as an "army" (independent of the "reserves") occurs also in Chapter 1 of The Manifesto of the Communist Party,[22] written by Marx and Engels in 1848:

Modern Industry has converted the little workshop of the patriarchal master into the great factory of the industrial capitalist. Masses of labourers, crowded into the factory, are organised like soldiers. As privates of the industrial army they are placed under the command of a perfect hierarchy of officers and sergeants. Not only are they slaves of the bourgeois class, and of the bourgeois State; they are daily and hourly enslaved by the machine, by the overlooker, and, above all, by the individual bourgeois manufacturer himself. The more openly this despotism proclaims gain to be its end and aim, the more petty, the more hateful and the more embittering it is. — Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party, 1848[22]

19 years later, in 1867, Marx introduced a more fleshed-out concept of the reserve army of labour in chapter 25 of the first volume of Capital: Critique of Political Economy.[4] Marx stated the following:

It is not merely that an accelerated accumulation of total capital, accelerated in a constantly growing progression, is needed to absorb an additional number of labourers, or even, on account of the constant metamorphosis of old capital, to keep employed those already functioning. In its turn, this increasing accumulation and centralisation becomes a source of new changes in the composition of capital, of a more accelerated diminution of its variable, as compared with its constant constituent. This accelerated relative diminution of the variable constituent, that goes along with the accelerated increase of the total capital, and moves more rapidly than this increase, takes the inverse form, at the other pole, of an apparently absolute increase of the labouring population, an increase always moving more rapidly than that of the variable capital or the means of employment. But in fact, it is capitalistic accumulation itself that constantly produces, and produces in the direct ratio of its own energy and extent, a relatively redundant population of labourers, i.e., a population of greater extent than suffices for the average needs of the self-expansion of capital, and therefore a surplus population. [...] The number of labourers commanded by capital may remain the same, or even fall, while the variable capital increases. This is the case if the individual labourer yields more labour, and therefore his wages increase, and this although the price of labour remains the same or even falls, only more slowly than the mass of labour rises. Increase of variable capital, in this case, becomes an index of more labour, but not of more labourers employed. It is the absolute interest of every capitalist to press a given quantity of labour out of a smaller, rather than a greater number of labourers, if the cost is about the same. In the latter case, the outlay of constant capital increases in proportion to the mass of labour set in action; in the former that increase is much smaller. The more extended the scale of production, the stronger this motive. Its force increases with the accumulation of capital. — Karl Marx, Capital: Critique of Political Economy, Volume I, Chapter 25 (1867)[4]

However, as Marx develops the argument further it also becomes clear that, depending on the state of the economy, the reserve army of labour will either expand or contract, alternately being absorbed or expelled from the employed workforce:

Taking them as a whole, the general movements of wages are exclusively regulated by the expansion and contraction of the industrial reserve army, and these again correspond to the periodic changes of the industrial cycle. They are, therefore, not determined by the variations of the absolute number of the working population, but by the varying proportions in which the working-class is divided into active and reserve army, by the increase or diminution in the relative amount of the surplus-population, by the extent to which it is now absorbed, now set free. — Karl Marx, Capital: Critique of Political Economy, Volume I, Chapter 25 (1867)[4]

Marx concludes as such:

The industrial reserve army, during the periods of stagnation and average prosperity, weighs down the active labour-army; during the periods of over-production and paroxysm, it holds its pretensions in check. Relative surplus population is therefore the pivot upon which the law of demand and supply of labour works. It confines the field of action of this law within the limits absolutely convenient to the activity of exploitation and to the domination of capital. — Karl Marx, Capital: Critique of Political Economy, Volume I, Chapter 25 (1867)[4]

Summary

In the above passages, Marx gave the idea its fleshed-out form, still used today, establishing:

- Even though total capital increases, the mass of constant capital grows faster than variable capital.

- This means that the organic composition of capital (the ratio of constant to variable capital, or c/v) will increase.

- Fewer workers can produce all that is necessary for society's requirements.

- Capital will become more concentrated and centralized into fewer hands.

- This is an absolute historical tendency under capitalism.

- Part of the working population will tend to become surplus relative to the requirements of capital accumulation.

- This surplus part of the population will grow proportionately to the part of the population still necessary for capital accumulation.

- The larger the wealth of society, the larger the reserve army of labour will become.

- The larger the wealth of society, the more non-working people it can support .

- The larger the wealth of society, the more unproductive labour it can support (i.e. labour which does not produce surplus value).

- The availability of labour influences wage rates and the larger the unemployed workforce grows, the more this forces down wage rates

- conversely, if there are plenty jobs available and unemployment is low, this tends to raise the average level of wages.

After Marx and Engels

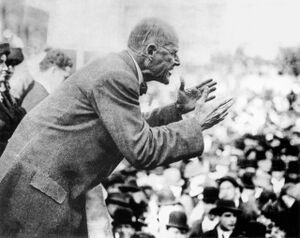

Eugene Victor Debs

“There Should Be No Aristocracy in labour’s Ranks” (1894)

In a January 1894 speech given to the railway employees[24] at the Knights of labour union hall in Ft. Wayne, Indiana, Eugene V. Debs spoke of an "army of scabs:"

Organizations are growing weaker and weaker day by day. At least 5,000 engineers and firemen are at present out of work. The policy of railway corporations for years has been to create a surplus in the ranks of labour . . . The only thing for railway men to do is get together. For 30 years we have been organized, and every strike has added to the great army of scabs, and cost the organization millions in money. Capital has profited by its disasters but labour has had the reverse. We must unite the train service with the track, shop, and clerical forces, and until we do that we must expect defeat. — Debs, 1894

How Long Will You Stand It? (1903)

In his December 1903 speech at the Chicago Coliseum,[23] Debs spoke of a "reserve army of capitalism:"

The Chicago City Railway employees were organized as thoroughly as they can be . . . But they lost. Why? Because there is a vast body of men always out of work under the capitalist system. It is called the reserve army of capitalism, and can be drawn on at will. If a hundred thousand or two hundred thousand men lay down their tools and give up their places of employment there are the same number always ready to take their places. — Debs, 1903

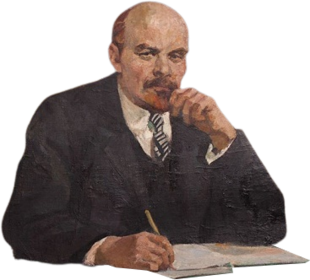

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin

The Economic Content of Narodism (1894)

In one of his earliest published political works, The Economic Content of Narodism and the Criticism of it in Mr. Struve’s Book (The Reflection of Marxism in Bourgeois Literature) (1894),[5] Lenin says the following:

. . .we know that poverty is created by capitalism itself at a stage of its development prior to the factory form of production, prior to the stage at which the machines create surplus population; secondly, the form of social structure preceding capitalism—the feudal, serf system—itself created a poverty of its own, one that it handed down to capitalism . . . Capitalist over-population is due to capital taking possession of production; by reducing the number of necessary workers (necessary for the production of a given quantity of products) it creates a surplus population . . . The formation of a reserve army of unemployed is just as necessary a result of the use of machinery in bourgeois agriculture as in bourgeois industry.[5]

— Lenin, 1894

A Characterisation of Economic Romanticism (1897)

In A Characterisation of Economic Romanticism (1897,[12] Lenin stresses that capitalism cannot develop without a reserve army of labour, and criticises the Narodnik economists for failing to reach the same conclusion:

. . . The analysis showed that surplus population, being undoubtedly a contradiction (along with surplus production and surplus consumption) and being an inevitable result of capitalist accumulation, is at the same time an indispensable component part of the capitalist machine. The further large-scale industry develops the greater is the fluctuation in the demand for workers, depending upon whether there is a crisis or a boom in national production as a whole, or in any one branch of it. This fluctuation is a law of capitalist production, which could not exist if there were no surplus population (i.e., a population exceeding capitalism’s average demand for workers) ready at any given moment to provide hands for any industry, or any factory. The analysis showed that a surplus population is formed in all industries into which capitalism penetrates and in agriculture as well as in industry—and that the surplus population exists in different forms. There are three chief forms: 1) Floating overpopulation. To this category belong the unemployed workers in industry. As industry develops their numbers inevitably grow. 2) Latent overpopulation. To this category belong the rural population who lose their farms with the development of capitalism and are unable to find non-agricultural employment. This population is always ready to provide hands for any factory. 3) Stagnant overpopulation. It has “extremely irregular” employment, under conditions below the average level. To this category belong, mainly, people who work at home for manufacturers and stores, including both rural and urban inhabitants. The sum-total of all these strata of the population constitutes the relative surplus population, or reserve army. The latter term distinctly shows what population is referred to. They are the workers needed by capitalism for the potential expansion of enterprises, but who can never be regularly employed.

Thus, on this problem, too, theory arrived at a conclusion diametrically opposed to that of the romanticists. For the latter, the surplus population signifies that capitalism is impossible, or a “mistake.” Actually, the opposite is the case: the surplus population, being a necessary concomitant of surplus production, is an indispensable attribute to the capitalist economy, which could neither exist nor develop without it [. . .] While noting the formation of a surplus population in post-Reform Russia, the Narodniks have never raised the issue of capitalism’s need of a reserve army of workers. Could the railways have been built if a permanent surplus population had not been formed? It is surely known that the demand for this type of labour fluctuates greatly from year to year. Could industry have developed without this condition? (In boom periods it needs large numbers of building workers to erect new factories, premises, warehouses, etc., and all kinds of auxiliary day labour, which constitutes the greater part of the so-called outside non-agricultural employments.) Could the capitalist farming of our outlying regions, which demands hundreds of thousands and millions of day labourers, have been created without this condition? And as we know, the demand for this kind of labour fluctuates enormously. Could the entrepreneur lumber merchants have hewn down the forests to meet the needs of the factories with such phenomenal rapidity if a surplus population had not been formed? (Lumbering like other types of hired labour in which rural people engage is among the occupations with the lowest wages and the worst conditions.) Could the system, so widespread in the so-called handicraft industries, under which merchants, mill owners and stores give out work to be done at home in both town and country, have developed without this condition? In all these branches of labour (which have developed mainly since the Reform) the fluctuation in the demand for hired labour is extremely great. Yet the degree of fluctuation in this demand determines the dimensions of the surplus population needed by capitalism. The Narodnik economists have nowhere shown that they are familiar with this law.

— Lenin, 1897

The Development of Capitalism in Russia (1899)

In The Development of Capitalism in Russia (1899),[6] Lenin comments on the reserve army of labour on several occasions. Lenin quotes a local agricultural investigator in Novorossia (modern day Ukraine) by the name of Tezyakov:

As regards Novorossia, local investigators note here the usual consequences of highly developed capitalism. Machines are ousting wage-workers and creating a capitalist reserve army in agriculture. “The days of fabulous prices for hands have passed in Kherson Gubernia too. Thanks to . . . the increased spread of agricultural implements . . .” (and other causes) “the prices of hands are steadily falling” . . . "The distribution of agricultural implements, which makes the large farms independent of workers the workers in a difficult position”[6][9] — Tezyakov, 1896 (as quoted by Lenin)

Having referenced the creation of a reserve army of agricultural wage workers in semi-feudal 1890s Novorossia, and having cited a local economic authority in Novorossia who openly used this term, Lenin comments, "The same thing is noted by another Zemstvo Medical Officer, Mr. Kudryavtsev, in his work."[10] and proceeds to quote said work:

"The prices of hands . . . continue to fall, and a considerable number of migrant workers find themselves without employment and are unable to earn anything; i.e., there is created what in the language of economic science is called a reserve army of labour—artificial surplus-population” The drop in the prices of labour caused by this reserve army is sometimes so great that “many farmers possessing machines preferred” (in 1895) “to harvest with hand labour rather than with machines”[6] — Kudryatsev, 1895 (as quoted by Lenin)

In contrast with the bourgeoisie of the early 21st century, who often cover up the reserve army of labour[25] or reference the reserve army of labour without using the term itself,[26] the bourgeoisie of Imperial Russia, where Lenin grew up, were perfectly comfortable with using scientific socialist terminology to diagnose certain features of the development of capitalism in Russia. Having quoted Tsarist officials Tezyakov and Kudryatsev on the reserve army of labour developing in Imperial Russian agriculture, Lenin further comments:

More strikingly and convincingly than any argument this fact reveals how profound are the contradictions inherent in the capitalist employment of machinery![6] — Lenin, 1899

Lenin wanted his readers in 1899 to understand that the reserve army of labour sometimes causes the market price of the commodity labour-power to drop so low that capitalists will temporarily forgo taking advantage of the latest developments in the means of production, because they are too expensive compared with the market price of the labour-power commodity sold by the wage workers. This sacrificing of productivity and efficiency in order to take advantage of a temporary depression of wages is a contradiction of capital which Lenin saw as inherent to the development of productive technology under capitalism. Later in the same work, Lenin says:

if we presuppose the maximum development of capitalism, we must also presuppose the maximum facility for the transfer of workers from agricultural to non-agricultural occupations, we must presuppose the formation of a general reserve army from which labour-power is drawn by all sorts of employers.[6] — Lenin, 1899

Lenin wanted his readers in 1899 to understand that this reserve army of labour applied not merely to the seasonal work of the agricultural sectors the Tsarist officials Tezyakov and Kudryatsev had been writing about, but to all industries:

. . . it is quite wrong to discuss the freeing of the farmer’s winter time independently of the general question of capitalist surplus-population. The formation of a reserve army of unemployed is characteristic of capitalism in general, and the specific features of agriculture merely give rise to special forms of this phenomenon.[6] — Lenin, 1899

Lenin also analyzed the effects of domestic industry on the reserve army of labour:

it is extremely important to point to the significance of capitalist domestic industry in the theory of the surplus-population created by capitalism. No one has talked so much about the “freeing” of the Russian workers by capitalism as have [various] Narodniks, but none of them has taken the trouble to analyse the specific forms of the “reserve army” of labour that have arisen and are arising in Russia in the post-Reform period. None of the Narodniks has even noticed the trifling detail that home workers constitute what is, perhaps, the largest section of our “reserve army” of capitalism. By distributing work to be done in the home the entrepreneurs are enabled to increase production immediately to the desired dimensions without any considerable expenditure of capital and time on setting up workshops, etc. Such an immediate expansion of production is very often dictated by the conditions of the market, when increased demand results from a livening up of some large branch of industry . . . This error of the Narodniks is all the more gross in that the majority of them want to follow the theory of Marx, who most emphatically stressed the capitalist character of “modern domestic industry” and pointed especially to the fact that these home workers constitute one of the forms of the relative surplus-population characteristic of capitalism . . . A small example. In Moscow Gubernia, the tailoring industry is widespread (Zemstvo statistics counted in the gubernia at the end of the 1870s a total of 1,123 tailors working locally and 4,291 working away from home); most of the tailors worked for the Moscow ready-made clothing merchants. The centre of the industry is the Perkhushkovo Volost, Zvenigorod Uyezd. . . The Perkhushkovo tailors did particularly well during the war of 1877. They made army tents to the order of special contractors; subcontractors with 3 sewing-machines and ten women day workers “made” from 5 to 6 rubles a day. The women were paid 20 kopeks per day. “It is said that in those busy days over 300 women day workers from various surrounding villages lived in Shadrino (the principal village in the Perkhushkovo Volost)” . . . “At that time the Perkhushkovo tailors, that is, the owners of the workshops, made so much money that nearly all of them built themselves fine homes”. These hundreds of women day workers who, perhaps, would have a busy season once in 5 to 10 years, must always be available, in the ranks of the reserve army of the proletariat.[6] — Lenin, 1899

Lenin talks about lumber workers as members of the reserve army of labour in the context of the development of capitalism in Tsarist Russia:

Agriculture . . . constitutes an auxiliary source of income, although in all official statistics you will find that the people engage in farming. . . . All that the peasant gets to meet his essential needs is earned in felling and floating lumber for the lumber industrialists. But a crisis will set in soon: in some five or ten years, no forests will be left. . . .” “The men who work in the lumber camps are more like boatmen; they spend the winter in the forest-encircled lumber camps . . . and in the spring, having lost the habit of working at home, are drawn to the work of lumber floating; harvesting and haymaking alone make them return to their homes. . . .” The peasants are in “perpetual bondage” to the lumber industrialists. Vyatka investigators note that the hiring season for lumbering is usually arranged to coincide with tax-paying time, and that the purchase of provisions from the employer greatly reduces earnings. . . . “Both the tree-fellers and the wood-choppers receive about 17 kopeks per summer day, and about 33 kopeks per day when they work with their own horses. . . . This paltry pay is an inadequate remuneration for labour, if we bear in mind the extremely insanitary conditions under which it is done,” . . . Thus, the lumber workers constitute one of the big sections of the rural proletariat; they have tiny plots of land and are compelled to sell their labour-power on the most disadvantageous terms. The occupation is extremely irregular and casual. The lumbermen, therefore, represent that form of the reserve army (or relative surplus-population in capitalist society) which theory[4] describes as latent; a certain (and, as we have seen, quite large) section of the rural population must always be ready to undertake such work, must always be in need of it. That is a condition for the existence and development of capitalism. To the extent that the forests are destroyed by the rapacious methods of the lumber industrialists (which proceeds with tremendous rapidity), an ever-growing need is felt for replacing wood by coal, and the coal industry, which alone is capable of serving as a firm basis for large-scale machine industry, develops at an ever faster rate.[6] — Lenin, 1899

Lenin also discusses the effects of the development of industrial machinery on the reserve army of labour:

the multitude of small establishments, the retention of the tie with the land, the adherence to tradition in production and in the whole manner of living—all this creates a mass of intermediary elements between the extremes of manufacture and retards the development of these extremes. In large-scale machine industry all these retarding factors disappear; the acuteness of social contradictions reaches the highest point. All the dark sides of capitalism become concentrated, as it were: the machine, as we know, gives a tremendous impulse to the greatest possible prolongation of the working day; women and children are drawn into industry; a reserve army of unemployed is formed (and must be formed by virtue of the conditions of factory production) . . . Large-scale machine industry can only develop in spurts, in alternating periods of prosperity and of crisis. The ruin of small producers is tremendously accelerated by this spasmodic growth of the factory; the workers are drawn into the factory in masses during a boom period, and are then thrown out. The formation of a vast reserve army of unemployed, ready to undertake any kind of work, becomes a condition for the existence and development of large-scale machine industry.[6] — Lenin, 1899

Lenin discusses how fluctuation in the demand for specific kinds of labour, particularly railroad labour, expands and contracts the reserve army of labour:

The length of the Russian railway system increased from 3,819 kilometres in 1865 to 29,063 km. in 1890, i.e., more than 7-fold. . . The length of new railway opened per year differed considerably in different periods; for example, in the 5 years 1868-1872 8,806 versts of new railway were opened and in the 5 years1878-1882, only 2,221. The extent of this fluctuation enables us to judge what an enormous reserve army of unemployed is required by capitalism, which now expands, and then contracts the demand for labour.[6] — Lenin, 1899

Lenin criticises the Narodnik view of the development of Capitalism in Russia, particularly with respect to the reserve army of labour:

The data regarding the total number of wage-workers in all branches of the national economy bring out very clearly the basic error committed by the Narodnik economists . . . who have talked a great deal about capitalism “freeing” the workers, have not thought of investigating the concrete forms of capitalist over-population in Russia; as well as in the fact that they failed completely to understand that the very existence and development of capitalism in this country require an enormous mass of reserve workers . . . We have now estimated the total number of the various categories of wage-workers, but in doing so do not wish to say that capitalism is in a position to give regular employment to them all. There is not, nor can there be, such regularity of employment in capitalist society, whichever category of wage-worker we take. Of the millions of migratory and resident workers a certain section is constantly in the reserve army of unemployed, and this reserve army now swells to enormous dimensions—in years of crisis, or if there is a slump in some industry in a particular district, or if there is a particularly rapid extension of machine production, which displaces workers—and now shrinks to a minimum, even causing that “shortage” of labour which is often the subject of complaint by employers in some industries, in some years, in some parts of the country[6] — Lenin, 1899

The Capitalist System of Modern Agriculture (1910)

In The Capitalist System of Modern Agriculture (1910),[7] Lenin pointed out that the partial survival of serfdom under the developing capitalism of Imperial Russia (and to a lesser extent Germany) constituted a form of reserve army of labour, and also that the reserve army of labour consists not only of those workers who are unemployed, but of those workers who are under-employed, as well:

The question arises of the significance of these masses of proletarian “farmers” in the general system of agriculture. In the first place, they represent the link between the feudal and the capitalist systems of social economy, their close connection and their kinship historically, a direct survival of serfdom in capitalism. If, for example, we see in Germany and particularly in Prussia that the statistics of agricultural enterprises include plots of land (known as Deputatland) which the landlord gives the agricultural labourer as part of his wages, is this not a direct survival of serfdom? The difference between serfdom, as an economic system, and capitalism lies in the fact that the former allots land to the worker, whereas the latter separates the worker from the land; the former gives the worker the means of subsistence in kind (or forces him to produce them himself on his “allotment”), the latter gives the worker payment in money, with which he buys the means of subsistence. Of course, in Germany this survival of serfdom is quite insignificant compared with what we see in Russia with her notorious “labour-rent” system of landlord farming, nevertheless it is a survival of serfdom. The 1907 census in Germany counted 579,500 “agricultural enterprises” belonging to agricultural workers and day-labourers, and of these 540,751 belong to the group of “farmers” with less than two hectares of land. In the second place, the bulk of the “farmers” owning such insignificant plots of land that it is impossible to make a living from them, and which represent merely an “auxiliary occupation”, form part of the reserve army of unemployed in the capitalist system as a whole. It is, to use Marx’s term, the hidden form of this army. It would be wrong to imagine that this reserve army of unemployed consists only of workers who are out of work. It includes also “peasants” or “petty farmers” who are unable to exist on what they get from their minute farm, who have to try to obtain their means of subsistence mainly by hiring out their labour. Their kitchen garden or potato plot serves this army of the poor as a means of supplementing their wages or of enabling them to exist when they are not employed. Capitalism requires these “dwarf”, “parcellised” pseudo-farms so that without expense it can always have a mass of cheap labour at its disposal.[7]

— Lenin, 1910

Lenin's Karl Marx (1914)

In Karl Marx: A Brief Biographical Sketch With an Exposition of Marxism (1914),[8] Lenin says the following of the reserve army of labour:

Marx revealed the error made by all earlier classical political economists (beginning with Adam Smith), who assumed that the entire surplus value which is transformed into capital goes to form variable capital. In actual fact, it is divided into means of production and variable capital. Of tremendous importance to the process of development of capitalism and its transformation into socialism is the more rapid growth of the constant capital share (of the total capital) as compared with the variable capital share. By speeding up the supplanting of workers by machinery and by creating wealth at one extreme and poverty at the other, the accumulation of capital also gives rise to what is called the “reserve army of labour”, to the “relative surplus” of workers, or “capitalist overpopulation”, which assumes the most diverse forms and enables capital to expand production extremely rapidly. In conjunction with credit facilities and the accumulation of capital in the form of means of production, this incidentally is the key to an understanding of the crises of overproduction which occur periodically in capitalist countries—at first at an average of every 10 years, and later at more lengthy and less definite intervals. From the accumulation of capital under capitalism we should distinguish what is known as primitive accumulation: the forcible divorcement of the worker from the means of production, the driving of the peasant off the land, the stealing of communal lands, the system of colonies and national debts, protective tariffs, and the like. “Primitive accumulation” creates the “free” proletarian at one extreme, and the owner of money, the capitalist, at the other.[8] — Lenin, 1914

From a Publicist’s Diary (1917)

In From a Publicist’s Diary (Peasants and Workers) (1917),[27] Lenin brings up the reserve army of labour briefly when criticising the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries:

And what about a “ban” on wage-labour? This is a meaningless phrase, helpless, unwittingly naive wishful thinking on the part of downtrodden petty proprietors, who do not see that capitalist industry as a whole would come to a standstill if there were no reserve army of wage-labour in the countryside, that it is impossible to “ban” wage-labour in the villages while permitting it in the towns, and lastly, that to “ban” wage-labour means nothing but a step towards socialism.

Rosa Luxemburg

The Industrial Development of Poland (1898)

Rosa Luxemburg, in her work The Industrial Development of Poland (1898),[29] in between providing tables of economic statistics on the development of Capitalism in Poland, briefly describes the reserve army of labour as a main prerequisite for industrial development:

Thus, after all the main conditions of industrial development – a domestic market, means of transport, an industrial reserve army – had been called to life in the years 1860-1877, the supervening tariff policy created a hot-house atmosphere of monopoly prices that placed Russian and Polish industry in an absolute El Dorado of primitive capitalist accumulation. — Luxemburg, 1898

Speech to the Hanover Congress (1899)

In her 1899 speech to the Hanover Congress,[30] Rosa Luxemburg brought up the reserve army of labour while warning against the idea that worker-owned cooperatives are all that is needed to bring about Socialism:

[. . .] those who imagine that the cooperatives already contain the seed of a socialist order forget an important factor in the contemporary situation: the reserve army [of the unemployed]. Even if we suppose that cooperatives gradually put all capitalist enterprises out of business and replace them, we certainly cannot entertain the fantastic notion that, given the current market relationships, the demand for goods could be filled without a general plan to determine production relationships. The question of the unemployed would remain open, as before. — Luxemburg, 1899

The Militia and Militarism (1899)

In her 1899 work The Militia and Militarism,[31] Rosa Luxemburg argued against the idea, put forward by the opportunist Isegrim-Schippel, that militarism relieves economic pressure on society, specifically by shrinking the reserve army of labour:

Schippel considers the militarism of the present day to be economically indispensable because it ‘relieves’ the economic pressure on society [. . .] When he speaks of a ‘release’ of pressure, it is obvious that he is thinking of capitalism. And in this he is of course correct: for capitalism, one of the most important forms of investment is militarism; from capitalism’s point of view, militarism is indeed a ‘release’ of pressure. That Schippel here speaks as a real advocate of the interests of capitalism is revealed by the fact that he has found a qualified authority to support him in this point [. . .] How can this phenomenon [militarism] operate on behalf of the working class? Ostensibly in such a way as to rid it of a part of its reserve army, i.e. those who force down wages, by maintaining a standing army; in this way its working conditions improve. And what does this mean? Only this: in order to reduce the supply in the labour market, in order to restrict competition, the worker in the first place gives away a portion of his salary in the form of indirect taxes in order to maintain his competitors as soldiers. Secondly, he makes his competitor into an instrument with which the capitalist state can contain, and if necessary suppress bloodily, any move he makes to improve his situation (strikes, coalitions, etc.); and thus this instrument can thwart the very same improvement in the worker’s situation for which, according to Schippel, militarism was necessary. Thirdly, the worker makes this competitor into the most solid pillar of political reaction in the State and thus of his own enslavement.

In other words, by accepting militarism, the worker prevents his wages from being reduced by a certain amount, but in return is largely deprived of the possibility of fighting continuously for an increase in his wage and an improvement of his situation. He gains as a seller of his labour, but at the same time loses his political freedom of movement as a citizen, so that he must ultimately also lose as the seller of his labour. He removes a competitor from the labour market only to see a defender of his wage slavery arise in his place; he prevents his wages being lowered only to find that the prospects both of a permanent improvement in his situation and of his ultimate economic, political and social liberation are diminished. This is the actual meaning of the ‘release’ of economic pressure on the working class achieved by militarism. Here, as in all opportunistic political speculation, we see the great aims of socialist class emancipation sacrificed to petty practical interests of the moment, interests moreover which, when examined more closely, prove to be essentially illusory.

— Luxemburg, 1899

The National Question (1909)

In The National Question[28] (1909), Rosa Luxemburg argues against the idea that a universal "right to work" (and therefore an end to the reserve army of labour) could ever be instituted with reformism, and specifically points to failed attempts by Utopian socialists to implement a universal "right to work" in the 1840s:

Actually, even if as socialists we recognized the immediate right of all nations to independence, the fates of nations would not change an iota because of this. The “right” of a nation to freedom as well as the “right” of the worker to economic independence are, under existing social conditions, only worth as much as the “right” of each man to eat off gold plates, which, as Nicolaus Chernyshevski wrote, he would be ready to sell [such "rights"] at any moment for a ruble. In the 1840s the “right to work” was a favorite postulate of the Utopian Socialists in France, and appeared as an immediate and radical way of solving the social question. However, in the [French] Revolution of 1848 that “right” ended, after a very short attempt to put it into effect, in a terrible fiasco, which could not have been avoided even if the famous “national work-shops” had been organized differently. An analysis of the real conditions of the contemporary economy, as given by Marx in his Capital, must lead to the conviction that even if present-day governments were forced to declare a universal “right to work,” it would remain only a fine-sounding phrase, and not one member of the rank and file of the reserve army of labour waiting on the sidewalk would be able to make a bowl of soup for his hungry children from that right. — Luxemburg, 1909

Accumulation of Capital (1913)

In her 1913 work The Accumulation of Capital,[32] Rosa Luxemburg describes "The first comprehensive analysis of the accumulation of individual capitals" given by Karl Marx in Capital, Volume I.[33] She breaks Marx's analysis into four interrelated parts, one of which is the reserve army of labour, which she describes as "both a consequence and a prerequisite of the process of accumulation."

[In his analysis,] Marx treats of (a) the division of the surplus value into capital and revenue; (b) the circumstances which determine the accumulation of capital apart from this division, such as the degree of exploitation of labour power and labour productivity; (c) the growth of fixed capital relative to the circulating capital as a factor of accumulation; and (d) the increasing development of an industrial reserve army which is at the same time both a consequence and a prerequisite of the process of accumulation.

Later in the same work,[34] she breaks down the sources of the reserve army of labour:

Marx himself has most brilliantly shown that natural propagation cannot keep up with the sudden expansive needs of capital. If natural propagation were the only foundation for the development of capital, accumulation, in its periodical swings from overstrain to exhaustion, could not continue, nor could the productive sphere expand by leaps and bounds, and accumulation itself would become impossible. The latter requires an unlimited freedom of movement in respect of the growth of variable capital equal to that which it enjoys with regard to the elements of constant capital—that is to say it must needs dispose over the supply of labour power without restriction. Marx considers that this can be achieved by an ‘industrial reserve army of workers’. His diagram of simple reproduction admittedly does not recognise such an army, nor could it have room for it, since the natural propagation of the capitalist wage proletariat cannot provide an industrial reserve army. Labour for this army is recruited from social reservoirs outside the dominion of capital—it is drawn into the wage proletariat only if need arises. Only the existence of non-capitalist groups and countries can guarantee such a supply of additional labour power for capitalist production. Yet in his analysis of the industrial reserve army Marx only allows for (a) the displacement of older workers by machinery, (b) an influx of rural workers into the towns in consequence of the ascendancy of capitalist production in agriculture, (c) occasional labour that has dropped out of industry, and (d) finally the lowest residue of relative over-population, the paupers. All these categories are cast off by the capitalist system of production in some form or other, they constitute a wage proletariat that is worn out and made redundant one way or another.

Anti-Critique (1915)

In Chapter 4 of her 1915 Anti-Critique,[35] written while interned in the women’s prison in Barnimstrasse, Berlin, Rosa Luxemburg, arguing against the economic theories of Otto Bauer, pointed out that a large industrial reserve army is contrary to high wages, while Bauer was arguing that employment should be at its highest when wages are at their lowest:

What sort of a remarkable economic law for the movement of wages is it, that they must ‘continually fall’ ‘until the entire working class is employed’? We are now experiencing a curious phenomenon: that the lower the wages fall the higher the level of employment rises. When wages reach their lowest point the entire reserve army will be absorbed! In real life the normal course of events is quite the opposite; a fall in wages corresponds with growing unemployment, a rise with increasing employment. The industrial reserve army is usually at its largest when wages reach their lowest level, and it is more or less absorbed when wages reach their highest level. — Luxemburg, 1915

Joseph Stalin

Marxism Versus Liberalism: An Interview With H.G. Wells (1934)

In Marxism Versus Liberalism: An Interview With H.G. Wells (1934),[36] Stalin, when criticising H.G. Wells's fundamentally reformist conception of Socialism, and by extension Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, uses the reserve army of unemployed as an example of why there cannot be socialist economic planning under a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie:

The United States is pursuing a different aim from that which we are pursuing in the USSR [. . .] Subjectively, perhaps, these Americans think they are reorganising society; objectively, however, they are preserving the present basis of society.That is why, objectively, there will be no reorganisation of society. Nor will there be planned economy. What is planned economy? What are some of its attributes? Planned economy tries to abolish unemployment. Let us suppose it is possible, while preserving the capitalist system, to reduce unemployment to a certain minimum.But surely, no capitalist would ever agree to the complete abolition of unemployment, to the abolition of the reserve army of unemployed, the purpose of which is to bring pressure on the labour market, to ensure a supply of cheap labour. Here you have one of the rents in the "planned economy" of bourgeois society. Furthermore, planned economy presupposes increased output in those branches of industry which produce goods that the masses of the people need particularly. But you know that the expansion of production under capitalism takes place for entirely different motives, that capital flows into those branches of economy in which the rate of profit is highest. You will never compel a capitalist to incur loss to himself and agree to a lower rate of profit for the sake of satisfying the needs of the people. Without getting rid of the capitalists, without abolishing the principle of private property in the means of production, it is impossible to create planned economy. — Stalin, 1934

Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR (1951)

In Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR (1951),[37] Stalin points out that Capitalist countries only take the employed portion of the proletariat into account and ignore the reserve army of labour when assessing their own living standards:

Usually, when speaking of the living standards of the working class [in capitalist countries], what is meant is only the standards of employed workers, and not of what is known as the reserve army of unemployed. Is such an attitude to the question of the living standards of the working class correct? I think it is not. If there is a reserve army of unemployed, whose members cannot live except by the sale of their labour-power, then the unemployed must necessarily form part of the working class; and if they do form part of the working class, then their destitute condition cannot but influence the living standards of the workers engaged in production. I therefore think that when describing the living standards of the working class in capitalist countries, the condition of the reserve army of unemployed workers should also be taken into account. — Stalin, 1951

Bourgeois Ideology

Regarding the reserve army of labour, the bourgeoisie have taken various strategic and ideological positions. These positions can typically be divided into the forms they take, which are denialist, obscurantist, and apologetic.

Bourgeois denialism

The bourgeoisie often denies...

- ...that the reserve army of labour is a necessary feature of capitalism.

- For example, the U.S. American professor of bourgeois economics Thomas Nixon Carver, writing in a 1927 article,[38] upheld a pretense of moderation by suggesting that both ruthless capitalists and their proletarian opponents are guilty of claiming that the reserve army of labour is necessary for capitalism to function. Carver charged that these two groups engage in similar rhetoric for contrary reasons:

Carver went on to answer both the brutally honest bourgeoisie, who admit to the existence of a reserve army of labour as a necessary condition of capitalism, as well as their proletarian opponents, with a denialist position:Two distinct groups are in the habit of insisting that an industrial reserve army, or a normal surplus of labourers, is necessary to the maintenance of the present industrial system. First, there are certain employers of labour who find it very convenient to their purposes to be able to hire and fire, to increase or decrease their labour force according as business is brisk or dull.[g] Some of these are doubtless honestly unable to imagine how they could do business in any other way. They really think that their business would be ruined if there were no normal surplus of labourers who might be called in when business was especially active and orders were coming in rapidly, and discharged when orders for new goods were diminishing. Consequently, they state, almost as an axiom, that such a labour reserve is essential to modern industry. Second, there are certain enemies of the present industrial system who accept as true these statements of the employers, and then use them as a basis for attacking the whole system and insisting on a new economic order.

Carver, apparently believed sincerely in meritocracy and went on to suggest that intelligent, strong bourgeoisie (as opposed to weak, stupid bourgeoisie) have no need of an industrial reserve army, even if it is convenient, and that an industrial reserve army would only push weak employers out of competition:If, they insist, the present industrial system can not exist without a normal condition of unemployment for large numbers of men, or if it can only employ all labourers in boom times, then the present industrial system is not fit to exist. If the original assumption were true, this conclusion would probably be unassailable.[h] The assumption happens to be false.

Carver went on to suggest class collabourationism as the solution to the problem.[. . .]if there were no industrial reserve army certain weak employers might go to the wall, and others have their profits reduced. But while the employers' difficulties might be increased if there were no labour reserve, the superior intelligence of the surviving employers might be able to meet them. That is what employing intelligence is for--to solve problems and meet difficulties. This, of course, only presents an alternative, but it is something to show that there is an alternative, or that it is not a foregone conclusion that industry must cease to exist if there is no labour reserve.[i]

Carver spends the rest of the article arguing against the importation of cheap labour (particularly in the form of immigration), and regularly attempts to demonstrate to his intended audience that the working class would be better off if unemployment were low. However, is never able to show how the working class being better off is also good for the capitalist class, except from the standpoint of nationalism. He attempts to appeal to the bourgeoisie's feelings of moral duty to the proletariat of the nation:[. . .] some of the older British economists, before Adam Smith put things in a true perspective, were in the habit of looking at the problem of national economy wholly from the standpoint of the upper classes. Consequently, they fell into the error of including an abundant supply of cheap labour, along with soil, mines, and other natural resources, among the factors that made for national wealth. Even today we occasionally hear a belated voice proclaiming that we must have cheap labour to make a prosperous nation [. . .] All this overlooks the fact that cheap labour means poverty instead of riches for the wage workers who, man for man, must be reckoned as of equal importance with the business and professional men, scholars, and artists.[j]

When labourers generally are barely able to afford the basic necessaries of life, they are likely to sacrifice the comfortable feeling of independence by accepting jobs that are confining, that offer few opportunities for diversion, or that put them under the domination of an overbearing boss. But when labourers are generally well paid, have money in their pockets, and are able to supply their families not only with the basic necessaries of life, but with numerous comforts and luxuries beside, then the comfort or luxury of feeling independent comes into their field of choice. An overbearing boss will then have a harder time filling his shop than the boss who treats his men as comrades in a common enterprise.[k]

- For example, the U.S. American professor of bourgeois economics Thomas Nixon Carver, writing in a 1927 article,[38] upheld a pretense of moderation by suggesting that both ruthless capitalists and their proletarian opponents are guilty of claiming that the reserve army of labour is necessary for capitalism to function. Carver charged that these two groups engage in similar rhetoric for contrary reasons:

- ...the very existence of a reserve army of labour, or surplus population of unemployed workers.

- ...that they use the reserve army of labour as scabs.

- ...that the reserve army of labour has a significant effect on the economy.

- ...that it is possible (only in a post-capitalist society[l]) to give all able-bodied adults meaningful employment doing productive labour.

- ...that it is in their class interests to maintain a reserve army of labour.

- ...that there is a high rate of unemployment.

Bourgeois obscurantism

The bourgeoisie will undertake a number of strategies to hide or obscure the reserve army of labour and its effects. This strategy is different from outright denialism, in that it centers on the action of obscuring, excluding or restricting access to available information, rather than the rhetoric of denying the truth of available information once it has been revealed. The forms bourgeois obscurantism often takes with respect to the reserve army of labour often include...

- ... removing people who have stopped looking for work from official unemployment statistics (even if they would accept a job if offered one).[25]

- ... ignoring the statistical significance of the mass of under-employed workers who require more hours since they are not making enough money to subsist.[25]

Bourgeois apologetics

Contrary to the above two strategies, there exists a third strategy which does not seek to deny or obscure the reserve army of labour, but rather to acknowledge, justify, and embrace the reserve army of labour, sometimes even going so far as to suggest that the reserve army of labour is good for society as a whole and not merely good for the bourgeoisie, thereby conflating the class interests of the bourgeoisie with the interests of the proletariat.

- Originally GATT was set up as a temporary body to facilitate trade negotiations. The International Trade Organisation (ITO) had instead been created to break down trade barriers, govern trade during negotiations, and resolve trade disputes. The ITO Charter, adopted at the U.N. Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTE) in 1948, included (among other "leftist" principles) a provision that all nations should maintain full employment. This provision outraged the U.S. and U.K.; both calling it socialistic and a violation of national sovereignty. In 1950, the U.S. government refused to ratify the agreement, and the ITO died [40]

- Here, we can see a blatant instance of the international bourgeoisie colluding to frame the full employment of the proletariat of all nations as somehow being harmful to society (specifically the bourgeois ideal of national sovereignty).

- Real estate CEO Tim Gurner openly advocated for a reserve army of labour during an onstage appearance at the Australian Financial Review’s Property Summit:[39]