Freikorps

Freikorps [FRY-kor] (German: “free corps”) were paramilitary groups formed by the Weimar government which played a major role in the politics and street fighting of interwar Germany. Although the decentralized movement had many apolitical members, most Freikorps groups were right-wing, nationalist, and fanatically anti-communist. The Weimar Social-Democratic government repeatedly deployed Freikorps groups against left-wing uprisings, including the Spartacus Uprising, the Bavarian Soviet, and the Ruhr Uprising. As many as 1.5 million men participated in Freikorps formations and their associated organizations between November 1918 and December 1923, after which the movement significantly declined. The National Socialist Party took much of its ideology, membership, and symbolism, including the use of the swastika, from the Freikorps movement.

The first Freikorps were formed in late November 1918 out of former imperial army formations. The Freikorps' first major deployment under the direction of Social Democrat Gustav Noske was during the January 1919 Spartacus Uprising led in part by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. The Freikorps and German Army bloodily suppressed the revolt and killed thousands of leftists, including Luxemburg and Liebknecht. The quick and harsh suppression of Spartacus League and the subsequent campaign against the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council movement in northern and central Germany earned the Freikorps a reputation for violence. Domestically, their primary objective was to crush the disruptive trade union and communist activity that openly opposed Social Democrat Friedrich Ebert’s government, but they also played a role in the attempt to suppress Polish separatism in the Upper Silesia conflict. In 1920, a Freikorps group led by Wolfgang Kapp and Walther von Lüttwitz attempted to overthrow the state in the so-called Kapp Putsch. The putsch attempt collapsed after a general strike from leftists and social democrats, but leftists who continued to resist the Weimar government after the fall of the coup were brutally suppressed by government forces with the help of Freikorps groups.

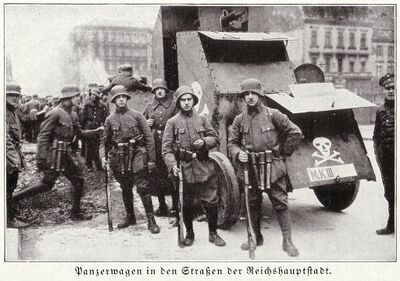

The Freikorps formed directly from the imperial army retained many First World War veterans and were generally loyal to the army high command. Some were formed temporarily in response to emergencies and dissolved shortly after their purpose had been served. Yet others were organized by former officers and soldiers independently of the Weimar government. Formations with significant military hardware such as armoured cars, artillery, mortars, and machine guns were deployed against insurrectionary leftists or Polish paramilitaries. Freikorps formations were also active outside of Germany’s borders, particularly in the Baltic states of Latvia and Estonia from March to July 1919. Fiercely independent, and increasingly radical in their nationalist sentiment, the actions of the renegade Baltic Freikorps significantly influenced the government’s perception of the paramilitary movement thereafter.

Following Freikorps involvement in the failed Kapp Putsch in March 1920, General Hans von Seeckt purged the vast majority of Freikorps troops from the Reichswehr and restricted future access to any government funds or equipment. The end of government approval and assistance had a powerful effect on the nature of the Freikorps and prompted their transition from a functional military organization into an illegal, violent social and political movement. With the loss of crucial government support, Freikorps members began to drift away from their units until only a very small, but highly politically motivated core remained by 1921. By 1923, the structural organization of Freikorps units had changed drastically from their immediate postwar form. By and large the major military capabilities of the Freikorps no longer existed and instead they tended to operate as “political combat leagues” focused on propaganda activities, political assassinations, and dispersing socialist and communist meetings. Although still committed to the use of violence to achieve political objectives, after 1923 the Freikorps were more active in street fighting and pub brawls than attacking dissident communists.[clarification needed] Many members left the Freikorps movement either as private citizens or joined the other organizations, like the Stahlhelm Veterans Association or the National Socialist Sturmabteilung (SA).

During the 1920s, the Freikorps movement fed into the growing National Socialist movement and influenced its ideology. One Freikorps group took part in the 1923 failed Beer Hall Putsch. The Sturmabteilung, essentially the street gang of the National Socialist Party, had significant Freikorps elements, including its founder, Ernst Röhm. However, Hitler personally distrusted the organization and began to develop the SS. In 1934, during the Night of the Long Knives, Adolf Hitler and the SS eliminated key leaders of the SA, including Röhm and other former Freikorps members, replacing the ideological loose cannon with the disciplined Nazis of the SS. However, Freikorps memoirs ensured that the image of the "Freikorps fighter" continued to be a powerful political symbol among rightist circles into the late Weimar Republic. Even during the Nazi period, the symbol of the Freikorps fighter retained some of its political value. The Freikorps fighter became an easily manipulated symbol of nationalism, anti-communism, and militarized masculinity deployed by the NSDAP to co-opt the lingering social and political support of the once-powerful movement.

Gallery

Bibliography

- Bucholtz, Mattheis (7 Jul 2017). "Freikorps". International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1). Retrieved 31 Aug 2023.