Economics of the Soviet Union

| Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) |

|---|

| History |

| History of the USSR, Russian Revolution of 1917 (February Revolution, October Revolution), Collapse of the USSR |

| Politics |

| Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Bolshevism, (before 1950s) Marxism–Leninism, Revisionism (after 1956) |

| Economy |

| Economics of the Soviet Union, Five-Year Plans |

| Soviet Republics (from 1956 until dissolution) |

| Armenian SSR, Azerbaijan SSR, Byelorussian SSR, Estonian SSR, Georgian SSR, Kazakh SSR, Kirghiz SSR, Latvian SSR, Lithuanian SSR, Moldavian SSR, Russian SFSR, Tajik SSR, Turkmen SSR, Ukrainian SSR, Uzbek SSR |

Russian Empire

Economic development prior to World War I

Capitalist industry in the Russian Empire had some quite considerable development, particularly in the region of Donetz and the Dnieper in the south, in the Moscow region and in Petersburg. Fairly modern in type, it had high concentrations of production and of ownership and control. In the 1880s, Russian iron industry in the south, measured by their output, was greater than that in Germany, about half as large as those in the British industry, and even ⅗ of the size of American industry (who had much larger furnaces).

Infrastructure

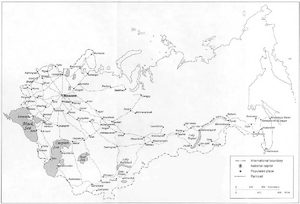

In the closing decade Russia had a good deal of rail construction completed. By 1903 it had ~40,000 miles of railroad. An impressive effort was made to increase connectivity across the Russian Empire. Such as between Moscow and the Pacific coast, the Trans-Siberian railway or the Turkestan railway across the trans-Caspian desert. Despite these results, however, Russia still lagged behind the rest of Europe, whether you measured in relation to area or population. There were less than 20,000 miles of road, and of these 3,000 were surfaced in the west-European manner. As regards to roads, Russia was still in the position that England was in the mid-eighteenth century.

Agriculture

An exporter of raw materials and an importer of finished manufactured goods, Russia's agriculture had been heavily influenced by the export market, and Russia's manufactures had mainly grown up in relation to a few urban markets of western Russia. Grain export relied on the poverty of the peasantry, which combined with the tax system to oblige the poorer peasants to flood local markets with grain at low prices immediately after the harvest in order to acquire cash with which to meet their taxes and to meet debts. At the same time, railway rates were adjusted favourably to transport of grain over long distances sold for export; and both railway companies and the State Bank granted credits against consignments of grain export. Just one of the many indicators of the tendency for Russian agriculture to become increasingly geared to the export market, rather than for domestic consumption.

Tsarist Russia experienced crippling low productivity in agriculture, which constituted four-fifths of the population's livelihood. Firstly was a very small portion of the land was being cultivated, around 25% compared to the 40% in France and Germany at the time. Average yield per acre of arable land in European Russia was about the same as with India. This combination of small arable land and lowness of yield resulted in a grain production appropriate for importing grain, not exporting it. This was further exasperated by the primitive farming techniques and the insufficiency of pasture available. The long winters limited the number of cattle peasants could maintain necessary for pasture. During a bad year, it was common for the straw from roofs to be fed to cattle, for the cattle to be slaughtered or to be sold. Many were without horses with which to plough and bring the harvest, or to take the produce to the market.

Prelude to 1917

1917 - 1927

War Communism

Transition to the New Economic Policy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

The New Economic Policy was part of what historian Brinton called the Thermidor after the French Revolution's Thermidorian Reaction.[tendency-based slant] It involved a variety of concessions to the backward strata of Soviet society, including the restoration of obstacles to divorce, laws against homosexuality, and the abolition of the age of consent laws.[1][tendency-based slant] Economically, it meant that industrial state owner enterprises gained autonomy in its policies while in rural areas individual private initiative and enterprise was allowed to dominate economic conduct.

In 1928 the NEP ended when the Soviet government implemented the first Five Year Plan. This became known as central planning, which lasted until circa 1991[citation needed] when the economy had reached a critical point in the crisis of the absolute over-accumulation of capital.[why?][tendency-based slant]

Economic Recovery

The 'Scissors' Crisis of 1923

Essentially, the Scissors crisis of 1923 marked a massive drop in wheat and crop prices while prices of industrial goods such as steel went up. This prompted the rapid industrialization process foreseen under Stalin

1928 - 1932

First Five Year Plan

Industrialization

1933 -1938

Second Five Year Plan

1945 - 1956

Third Five Year Plan

The Planning System

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

The Financial System

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

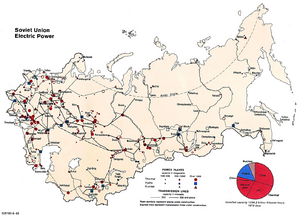

Locations of Industry

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

Trade Unions, Wages and Conditions of Labor

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. |

References

- ↑ Brinton, C. (1965). Template:Citation/make link. pp. 225–226. Brinton, C. (1965). The Anatomy of Revolution. pp. 225–226.

- Articles with insufficient sources from March 2024

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with slanted statements

- All articles with unsourced statements

- All articles to be expanded

- All articles with empty sections

- Articles using small message boxes

- History

- Political economy

- Economy of the USSR