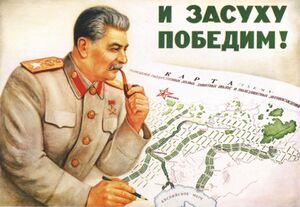

The Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature

The Great Plan for the Transformation of Nature was a massive environmental program prompted by Stalin to replant thousands of square kilometers of forests cut down or destroyed in preparation for and during the industrialization and World War II. It also established a modern system of nature reserves and replenished farmland. The Program was planned to go from 1949 to 1965 and plant thousands of kilometers of forest belts in the steppe regions of the USSR. The adoption of the draft was preceded by drought and famine of 1946-1947 prompting the program to begin a year early on the 20th of October, 1948. The plan would continue until Stalin's death in 1953.

Contents of the Plan

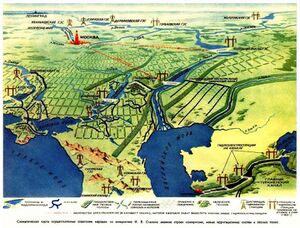

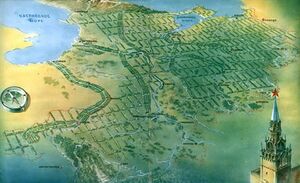

The plan was adopted on the initiative of Stalin and put into effect by the decree of the Council of Ministers of the USSR and the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks dated October 20, 1948. "On the plan of field-protective afforestation, the introduction of grass-field crop rotations, the construction of ponds and reservoirs for ensuring high sustainable yields in the steppe and forest-steppe regions of the European part of the USSR ”.[1][2][3][4] The plan had no precedents in the world experience in scale. In accordance with this plan, it was necessary to plant forest strips to block the road to dry winds and change the climate on an area of 120 million hectares. The central place in the plan was occupied by field-protective afforestation and irrigation. The project, calculated for the period 1949–1965, provided for the creation of eight large state forest belts in the steppe and forest-steppe regions with a total length of over 5300 kilometers (530000 hectares).

“The plan provides for the creation during 1950-1965. large state forest protection belts with a total length of 5320 km, with a forest plantation area of 112.38 thousand hectares.

These strips will pass:

1) on both banks of the river. The Volga from Saratov to Astrakhan - two lanes 100 m wide and 900 km long;

2) along the watershed pp. Khopra and Medveditsa , Kalitva and Berezovoy in the direction of Penza - Yekaterinovka - Kamensk (on the Seversky Donets ) - three lanes 60 m wide, with a distance between the lanes of 300 m and a length of 600 km;

3) along the watershed pp. Ilovli and Volga in the direction of Kamyshin - Stalingrad - three lanes 60 m wide, with a distance between the lanes of 300 m and a length of 170 km;

4) on the left bank of the river. The Volga from Chapaevsk to Vladimirovka - four lanes 60 m wide, with a distance between the lanes of 300 m and a length of 580 km;

5) from Stalingrad to the south on Stepnoy - Cherkessk - four lanes 60 m wide, with a distance between the lanes of 300 m and a length of 570 km, although at first it was conceived as the Kamyshin - Stalingrad - Stepnoy - Cherkessk forest belt, but due to certain technical difficulties, it was decided to split into 2 forest beltsKamyshin - Stalingrad along the river. Ilovlya and r.Volga and Stalingrad proper - Cherkessk and the Green Ring of Stalingrad as a connecting link between them;

6) along the banks of the river. Ural in the direction of Mount Vishnevaya - Chkalov - Uralsk - Caspian Sea - six lanes (three on the right and three on the left bank) 60 m wide, with a distance between the lanes of 200 m and a length of 1080 km;

7) on both banks of the river. Don from Voronezh to Rostov - two lanes 60 m wide and 920 km long;

8) on both banks of the river. Seversky Donetsfrom Belgorod to the river. Don - two lanes 30 m wide and 500 km long."[5]

The plan envisaged not only absolute food self-sufficiency for the Soviet Union, but also an increase in the export of domestic grain and meat products from the second half of the 1960s. The created forest belts and reservoirs were supposed to significantly diversify the flora and fauna of the USSR. Thus, the plan combined the tasks of protecting the environment and obtaining high sustainable yields.

Goals and Objectives

Until the middle of the last century, the so-called "Wild Field of Russia" or the steppes of the Azov and Black Sea regions, were a plain scorched by the sun. Such territories stretched far to the east - beyond the Don, beyond the Volga, into the Ural and Kazakh steppes. The steppe areas of the Soviet Union were periodically covered by the so-called "black storms". They usually appeared in early spring in dry weather on lands devoid of vegetation - that is, on the so-called "uplifted virgin soil". Powerful winds lift millions of tons of soil to the sky - more precisely, its smallest, dispersed particles - and carry it over great distances. For example, in the spring of 1928, in the central and southeastern regions of Ukraine, the Stalingrad and Astrakhan regions of the RSFSR, winds lifted over 15 million tons of the most valuable black soil into the air. At the same time, dust clouds rose to a height of up to a kilometer. As a result, the layer of black soil on the richest arable lands in the country decreased by 10-15 centimeters only at one time. In the last half century alone, such storms have raged in the steppe regions at least sixteen times. And at the beginning of the twentieth century and earlier, this happened even more often.

The purpose of this plan was to prevent such droughts, sand and dust storms by building reservoirs, planting forest protection plantations and introducing grass crop rotations in the southern regions of the USSR (Volga region, Western Kazakhstan, North Caucasus, Ukrainian SSR). This also served to increase the arability of the land, given the limitations of the land. In total, it was planned to plant more than 4 million hectares of forest and create state field protection belts over 5300 km long. These strips were supposed to protect the fields from hot southeastern winds - dry winds. In addition to state forest protective belts, forest belts of local importance were planted along the perimeter of individual fields, along the slopes of ravines, along existing and newly created reservoirs, on the sands (with the aim of fixing them). In addition, more progressive methods of processing fields were introduced: the use of black fallows, plowing and stubble plowing; correct system of application of organic and mineral fertilizers; sowing selected seeds of high-yielding varieties adapted to local conditions. The plan also provided for the introduction of a grass-field farming system developed by the outstanding Russian scientists V.V.Dokuchaev, P.A.Kostychev, and V.R. Williams. According to this system, part of the arable land in crop rotations was sown with perennial legumes and bluegrass herbs. Grasses served as a fodder base for animal husbandry and a natural means of restoring soil fertility.

For fifteen years of work, it was planned to create twenty-two forest protection belts with a total length of almost five and a half thousand kilometers along with 44,228 ponds and man-made reservoirs to be built. In the development of this plan, a number of special decrees were adopted to stimulate the construction and modernization of hydraulic structures. These include the construction of a cascade of hydroelectric power plants on the Volga, the Main Turkmen canal Amu-Darya - Krasnovodsk, the creation of the "Siberian Sea" - the connection of the Ob with the Irtysh, Tobol and Ishim with the help of a reservoir with an area of 260 square kilometers ("eight Netherlands"). Then, within the framework of the same plan, it was planned to build a water supply canal to the Aral Sea or rivers flowing into it. Work on the Siberian Sea began in 1950, but was suspended in 1951: Stalin doubted the environmental safety of the project, requesting the relevant details. He died before the research was completed.

Implimentation

Two decades of Soviet research and small-scale attempts along with the knowledge of the past century went into the project. The first strategic plan for the optimization of steppe nature management - the Dokuchaev plan to combat drought - dated back to the 19th century. This is the first plan for the conscious design of the steppe landscape, developed and started to be implemented in the 80s-90s of the 19th century by the Special Expedition to Test and Take into Account Various Methods and Techniques of Forestry and Water Management in the Steppes of Russia, at the initiative of the Free Economic Society. In 1892, a book by the head of the "Special Expedition" Vasily Vasilyevich Dokuchaev (1846-1903) "Our Steppes Before and Now" was published, which outlined a plan for transforming nature and agriculture of the steppe for a complete victory over drought; The main reason for droughts and crop failures was unsystematic agricultural exploitation of 'chernozem's, excessive plowing of steppes, deforestation on watersheds and, as a consequence, the development of planar and ravine erosion, a decrease in the level of groundwater, destruction of the lumpy-granular structure of the soil, deterioration of the introduction-air properties of chernozems, because of which they begin to retain atmospheric moisture worse, and it is easier to take it away in drought.

Dokuchaev initially intended to experimentally test his method of "landscape treatment" in three areas: Kamennaya Steppe, Velikoanadolskiy and Starobelskiy areas. This was coordinated and approved by the Russian Empire, the necessary funding given, and Dokuchaev received the opportunity to implement his project. According to his plan, 10–20% of the total territory of the steppe sites was subject to afforestation. Forest belts of various widths from 6 to 200 m were laid. By 1898, the experimental sites were afforestation.[6]

In 1903, Dokuchaev died, and together with his death, the implementation of his project ceases, although the forest belts planted by him continue to be maintained as part of the state forestry. Dokuchaev's plan was agricultural and was aimed at obtaining sustainable yields and preserving soil fertility through mass strip afforestation - creating a continuous network of forest belts of various ranks, structure and specific orientation, dividing the territory into rectangular sections and delineating beams and ravines, mass construction of reservoirs and the introduction of a grass field system agriculture. While some of this was put to work, the plan was not expansive. In 1917 the country had only 11 shelter belts in the fields. His work was not abandoned, with works by people like of Georgii Fedorovich Morozov, professor at the St. Petersburg Forest Institute, who criticized the reliance on German forest theory,[7] and proposed using the traditional Russian methods, with modernized application.

These ideas continued to live in society, actively supported by the Soviet government and it is environmental policies.[8] Excluding the period from 1918 to 1921 under War Communism - which demanded a raised expropriation of timber to fund and supply the war effort - and the brief period in 1929, the Bolsheviks lowered quotas for logging and heavily restricted exploitation of forests. The People's Commissariat of Agriculture (Narkomzem), acted as counter-balance to the The Supreme Soviet of the National Economy (VSNKh/Vesenkha) on the subject of felling and processing of timber for urban projects.

In the 30s, the Dokuchaev Research Institute of the Agricultural Chernozem Zone was organized at the Kamenostep station. His methods were polished and finished with newer research of the time. In 1928, in the Astrakhan semi-desert, scientists and foresters planted the first hectares of young trees with their own hands from scratch. And if in the open steppe the heat reached 53 degrees Celsius, then in the shade of the trees it was 20% cooler, soil evaporation decreased by 20%. Observations showed that a pine tree with a height of only 7.5 meters collected 106 kg of rime and hoarfrost during the winter. This, in turn, means that a small grove is able to "extract" from precipitation several tens of tons of moisture. In 1931, the Council of People's Commissars and the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks (Bolsheviks) adopted a resolution "On the Creation of Extensive Field-Protective Strip Plantations in Rainfed and Irrigated Areas."

"in July 1936 a new agency was founded, the Main Administration of Forest Protection and Afforestation (GLO) whose sole duty would be to look after lands henceforth called "water protective forests"...the head of the GLO and his two deputies were to be designated by Sovnarkom and would answer to that body alone, and only Sovnarkom could allow exceptions to the logging restrictions that the GLO established. Forbidden under threat of criminal responsibility was any cutting of the forest (aside from sanitary cutting) in vast zones..."[7]

In 1938, the Resolution of the Council of People's Commissars and the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) On Measures to Ensure a Sustainable Harvest in the Arid Regions of the Southeast of the USSR was published. By 1941 there were 468; From 1918 to 1941, 181 ravine-gully and 265 sand-strengthening plantations were created in the country. The War interrupted progress temporarily, as restrictions were rescinded to give unrestricted resources for the front, but by 1943, when the situation had stabilized the progress continued with new legislation.

"Soviet forest protection grew yet more robust - and achieved the form it would retain until the last day of 2006 - on April 23, 1943, when Sovnarkom reversed the temporary war-time legislation allowing increased logging and issued Decree № 430, dividing the nation's forests into three groups, two of which were subject to protective measures. Into Group I went "the forests of the state zapovedniki, soil protective, field protective, and resort forests, [and] forests of green zones around industrial firms and towns"; in these forests, only "sanitary cuts and selective cuts of overmature timber" were allowed, with clearcuts of all types forbidden. Into Group II went all the forests of Central Asia and along the left bank of the Volga; here, only cuts less than or equal to the annual growth, "ratified by Sovnarkom," were allowed. Group I and II forests remained under the control of the GLO. In Group III were grouped all other forests, on which no restrictions whatsoever were imposed."[7]

For the implementation of the plan, the workers of the forestry enterprises procured six thousand tons of seeds of tree and shrub species. Scientists have developed the compositions of forest belts. They included such trees as oak, birch, ash and small-leaved elm; accompanying - common elm, linden, Tatar maple, yellow acacia steppe cherry, tamarix, narrow-leaved elm, Tatar honeysuckle. To attract birds to forest belts, it was supposed to plant raspberries and golden currants.

The system of state forest belts was supplemented by afforestation in the fields of collective farms and state farms, for which special state loans were allocated to farms. In the long-term work, the relevant ministry developed machines for simultaneous seven-lane tree planting. Simultaneously with the installation of a system of field-protective afforestation, a large program was launched to create irrigation systems. In the USSR, about 4 thousand reservoirs were created, containing 1200 km³ of water. They made it possible to dramatically improve the environment, build a large system of waterways, regulate the flow of many rivers, receive a huge amount of cheap electricity, and use the accumulated water to irrigate fields and gardens.[9]

The Agrolesproekt Institute (now the Rosgiproles Institute ) was created to work out and implement the plan . According to his projects, four large watersheds of the basins of the Dnieper, Don, Volga, Ural, European south of Russia were covered with forests. The first state forest belt designed by Agrolesproekt stretches from the Ural mountain Vishnevaya to the Caspian coast, the length is more than a thousand kilometers. The total length of large state field protection belts exceeded 5300 km. In these zones, 2.3 million hectares of forest were planted.

According to the plan of the institute "Agrolesproekt", four large watersheds of the basins of the Dnieper, Don, Volga, Ural, European south of Russia were covered with forest. Simultaneously with the field-protective forest development, measures were taken to preserve especially valuable forest areas. Including Shipova forest, Khrenovsky pine forest, Borisoglebsky forest area, Tula abatis, Black forest in the Kherson region, Velikoanadolsky forest, Buzuluk pine forest. Forests and parks destroyed during the war were being restored. To solve the problems associated with the implementation of the five-year plan of land reclamation, the Moscow State University of Environmental Engineering was brought in.[10]

Results

The measures taken led to an increase in grain yield by 25-30%, vegetables - by 50-75%, grasses - by 100-200%. As a result of an increase in investment in agriculture and an improvement in the technical equipment of collective and state farms, it was possible to create a solid fodder base for the development of animal husbandry (machine and tractor stations played a significant role in this). Production of meat and lard in 1951 compared with 1948 increased by 80%, including pork - by 100%, milk production - by 65%, eggs - by 240%, wool - by 50%. As a result, the share of public animal husbandry of collective and state farms in the production of livestock products increased significantly: in 1950 it was 33% for meat, 25% for milk, 11% for eggs.[4] This was appropriate for the increasing consumptive needs of the USSR. The 4000 reservoirs created contained ~1200 km³ of water and allowed for a large system of waterways to manage the flow of rivers and provide cheap electricity, as well as accumulated moisture for farming.

Climatic changes have also become very evident. In the spring, during the snowmelt period, and in some cases in summer, during the rains, forest belts trapped surface runoff, transferring it into the subsurface runoff, which contributes to the replenishment of groundwater and an increase in their level. Reducing wind speeds as well as lumpy soil structure reduced unproductive evaporation from soil surface. As a result, the water regime of agricultural fields changed; receiving significant additional nutrition, producing an increased yield.

In general terms, the influence of forest plantations and agrotechnical measures on the water regime of rivers in the steppe and forest-steppe zones were expressed in the following:

- The spring flood in the rivers will be more extended due to the slowing down of melt water runoff in forest belts. The duration of the flood will increase, while the maximum flow rates and the volume of melt water runoff will decrease.

- The ground water supply of the rivers will increase and, accordingly, their water content in low-water periods will increase.

- Water erosion and the damage caused by it will sharply decrease: the flat soil washout will decrease and gully erosion will stop.

- The removal of chemically dissolved substances decrease.

Forest plantations reduced soil erosion, especially flat soil washout, and also prevented the formation of ravines. Due to the increase in the intensity of local moisture turnover, the amount of atmospheric precipitation increased. The first stages of the implementation of the plan proceeded quickly. In addition to state protective forest belts, the upper reaches of ravines and gullies were planted with trees and shrubs everywhere, the mouths of ravines were fixed with wattle fences and hedges. Ponds lined with trees were built in natural hollows. And to support the life of small rivers, dams with water mills and power plants were built. In forest-protected fields, up to 80 percent of moisture was absorbed into the soil. The unity of forest and field and the need for their unified management became obvious. Swamps were drained and cleaned into shallow ponds. The careful mixture of different tree and shrub species exemplified an implementation of what can be called Permaculture today.

Of course no plan of such scale can be executed perfectly and some mistakes are inevitable. While the trees served as a useful barrier to dry winds, they also funneled some winds along the steppe. Ecology of the era was in its infancy around the world and thus some features did not work out as planned. While in many areas it was successful in preserving land and increasing yield, in some others it instead decreased actual yield. In June 1949, at the suggestion of the Main Directorate of Field Protective Afforestation and the USSR Ministry of Forestry, it was decided to create industrial oak forests in the Astrakhan, Volgograd and Rostov regions on an area of 100, 137 and 170 thousand hectares, respectively (subsequently, industrial oak forests were created in the Stavropol Territory). It soon became clear that the economic effect from the creation of industrial oak forests can only be achieved on black soil, and under other conditions oaks do not take root well. By 1956, a little more than 15% of oak crops were preserved.

After Stalin

Almost immediately after his death, the plan was halted. Already in the 20th of April 1953, the USSR Council of Ministers issued a decree No. 1144, according to which all works on protective afforestation were suspended. In order to fulfill this legislative act, forest protection stations were liquidated, the positions of agromeliorators were reduced, plans for artificial forest plantations were excluded from the general reporting of all organizations, and the forest belts themselves were transferred to the land use of collective and state farms. In the same spring, such “Great construction projects of communism” as the Salekhard-Igarka railway, the Baikal-Amur mainline, the Krasnoyarsk-Yeniseysk tunnel, the Main Turkmen Canal and the Volga-Baltic waterway ceased to exist. Instead of the Main Turkmen Canal, the Karakum Canal was built in 1954 and contributed to the decline of the Aral Sea. In the next few years many forest belts were cut down, several thousand ponds and reservoirs, which were intended for fish breeding, were abandoned, 570 forest protection stations created from 1949 to 1955 were liquidated. The decision to terminate a number of large-scale construction projects, including hydrotechnical, was made by L.P. Beria and Khrushchev. The Ministry of Forests (Minleskhoz) was dissolved on March 15, 1953 - only six days after Stalin's funeral - and its assets transferred to the Ministry of Agriculture, The number of workers assigned to forestry in Moscow fell from 927 to 342 in the space of six months, (62%), and then to 120 workers after a year.[11]

Khrushchev, in his fervor to discredit his predecessor, belittled and attacked the plan, introducing pesticides and prompting the creation of chemical plants to imitate the USA's system. The result was much arable land became saline soil. The reservoirs poisoned and useful birds, animals and insects died. Cancer cases were on the rise among people. This culminated in 1962–1963, an ecological disaster occurred associated with soil erosion on virgin lands. A food crisis broke out in the country as prices rose prompting discontent and protests. One of the most notable was the suppressed 1962 Novocherkassk Revolt. In the fall of 1963, bread and flour disappeared from store shelves, and sugar supply interruptions began. In the same year, as a result of a poor harvest and a lack of reserves in the country, for the first time after the war, selling six hundred tons of gold from reserves in the USSR, about 13 million tons of grain were purchased abroad. Only after 1967 with Khruschev's abdication did the USSR return to the ideas of the plan, and start maintaining and supplementing what had been finished before Stalin's death. It can be concluded that Stalin was essentially a lynch-pin in the plan.

"When Stalin passed from the scene, supporters of forest protection apparently lost the one political actor in Soviet history who was both willing to confront the industrial bureaus and powerful enough to tip the balance in conservation's favor." - Stephen Brain, Stalin's Environmentalism pg 118 [7]

During the years of Gorbachev's Perestroika, work on the expansion and modernization of Soviet irrigation and forest plantation systems, was stopped, and the system itself began to collapse and become out of order as the socio-economic structure was destroyed. As a result, water supply to agriculture began to decline and since 2004 has been fluctuating at about 8 km³ - 3.4 times less than in 1984. In the 1980s, forests were planted in the forest belts in the amount of 30 thousand hectares per year, after 1995 it fluctuated at about 2 thousand hectares, and in 2007 it was 0.3 thousand hectares. The created forest belts are overgrown with bushes and lose their protective properties. Due to ownerlessness under the current Russian Federation, forest plantations are being cut down.[9] This causes further worsening in moisture loss, and in the surrounding areas, contributes to the Aral Sea's accelerated desertification.

“Until 2006, they were part of the structure of the Ministry of Agriculture , and then they were liquidated by status. Having turned out to be no-one, the forest belts began to be intensively cut down for cottage development or in order to obtain timber." - General Director of the Institute "Rosgiproles" Mikhail B. Voitsekhovsky[12]

However the plan's impact remains, as Russia's forests are massive expanses to this day, even as private companies cut down swathes for logging. Despite the gradual degradation, the forest belts continue to perform snow retention and dry-wind blocking functions to this day.[13] There are projects for their restoration and development, for example, the Green Wall of Russia project,[14] but the current Russian Federation and its systemic privatization makes the impact of these efforts low.

As of 2012 the conditions of these strips varies.

- The State protective forest belt from Saratov to Astrakhan on both banks of the Volga river was 100 meters wide and 900 kilometers long; Along the left bank of the Volga, this strip now runs from the town of Engels to the south to the border of the Saratov region with the Volgograd region. Unfortunately, the preserved strip is only about 120 km long, with little to the south of the Saratov region.

- The State protective forest belt in the direction of Penza - Yekaterinovka - Veshenskaya - Kamensk on the Northern Donets, on the watersheds of the Khopra and Medveditsa, Kalitva and Berezovaya rivers, consisting of three strips 60 meters wide each with a distance between the strips of 300 meters and a length of 600 kilometers; The strip has been preserved in its entirety and is in excellent condition. Today it is even longer than planned.

- The State protective forest belt in the direction Kamyshin - Stalingrad, on the watershed of the Volga and Ilovli rivers, consisting of three strips 60 meters wide each with a distance between the strips of 300 meters and a length of 170 kilometers; The very "youth track" planted by the Komsomol members, about which the newspapers wrote in 1953, has been preserved throughout. Kamyshin's condition is good, the closer to Volgograd, the more sparse.

- The State protective forest strip in the direction of Chapaevsk - Vladimirovka, consisting of four strips 60 meters wide each with a distance between the strips of 300 meters and a length of 580 kilometers; It is preserved and the plan was exceeded by 50 kilometers.

- The State protective forest belt in the direction of Stalingrad - Stepnoy - Cherkessk, consisting of four strips 60 meters wide each with a distance between the strips of 300 meters and a length of 570 kilometers; There is only a southern section of this strip from the river, from Manych to Cherkessk, surviving.

- The State protective forest belt in the direction of Vishnevaya Mountain - Chkalov - Uralsk - Caspian Sea along the banks of the Ural River, consisting of six lanes (3 on the right and 3 on the left bank) 60 meters wide each with a distance between the lanes of 100–200 meters and length of 1080 kilometers; Little is left of the protective strip. On the territory of the Orenburg region, stripes are still visible, but there are many bald spots and empty areas. The Kazakh portion is even more sparse.

Over all while large portions in the North remain, the Southeastern portions - poorly made for large trees - have declined heavily. Still, the surviving forest belts still give shelter to squirrels and hares, mushrooms and wild boars, songbirds, partridges and pheasants, and continue to defend large portions of the land - as there have been no 'black storms' in the several decades since the Plan was halted.

Notes

- The plan and its goals are similar to Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Great Plains Shelterbelt program, during the Great Depression, made to counteract the Dust Bowls of the Mid Western USA, by planting long lines of forest to halt the wind from sweeping away topsoil.[15] This was in part used as a proof-of-concept for Soviet Planners.

- In the current 2010s China is using a similar program also based on historical and modern concepts called the Three-North Shelter Forest Program to create walls of forest to block and remove smog and CO2 from the air by having thee military plant millions of acres of forest which has visibly reduced pollution levels in cities like Beijing.[16]

- Another similar project in Africa, aimed more at stopping desertification, is the Great Green Wall of the Sahara and the Sahel project, of the African Union which was in-part inspired by the Algerian Green Dam and previously mentioned Chinese Three-North Shelter Forest Program.[17]

References

- ↑ Большая Советская энциклопедия. Гл. ред. Б. А. Введенский, 2-е изд. Т. 16. Железо — Земли. 1952. 672 стр., илл.; 51 л. илл. и карт. (стр. 528)

- ↑ Охрана окружающей среды на примере государственного управления водными ресурсами — Сергей Якуцени — Google Книги

- ↑ 3960 "О плане полезащитных лесонасаждений, внедрения травопольных севооборотов, строительства прудов и водоёмов для обеспечения высоких и устойчивых урожаев в степных и лесост…

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Роль МТС в сельском хозяйстве СССР в первые послевоенные годы (1946—1952 гг.)

- ↑ https://ru.wikisource.org/wiki/Постановление_Совета_Министров_СССР_и_ЦК_ВКП(б)_от_20.10.1948_№_3960

- ↑ Moon, David (2005). Template:Citation/make link. London.

Moon, David (2005). The Environmental History of the Russian Steppes: Vasilii Dokuchaev and the Harvest Failure of 1891. London.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Brain, Stephen (2010). "Stalin's Environmentalism". The Russian Review. Wiley on behalf of The Editors and Board of Trustees of the Russian Review. 69 (1): 93–118. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ↑ Lenin, Vladimir (1917). Template:Citation/make link. Template:Citation/make link. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/tasks/ch08.htm#v24zz99h-071-GUESS. Lenin, Vladimir (1917). "8". The Tasks of the Proletariat in Our Revolution.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Засуха 2010 – третий экзамен". Русский обозреватель. 2010-08-05. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- ↑ Газета «Вечерняя Москва», 6 марта 1953 г.

- ↑ RGAE (РГАЕ), fond 538, op.1, d.1, 1.212, and d.2, 11.14 and 260. http://rgae.ru/novosti/k-50-letiyu-sozdaniya-gosudarstvennogo-komiteta-lesnogo-khozyaistva-sssr.shtml https://archive.is/FsHSP#selection-13153.12-13153.65

- ↑ Войцеховский Михаил Богданович (2008-08-05). "Государственная лесополоса". Независимая газета. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

- ↑ Пастернацкий, Валентин Андреевич. "Защита автомобильных дорог от снежных заносов насаждениями рациональных конструкций". Минск.

- ↑ Ponomarenko, Serguei (1/10/1994). "The Green Wall of Russia".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ https://livingnewdeal.org/glossary/shelterbelt-project-1934/

- ↑ https://www.treehugger.com/chinese-troops-deployed-plant-trees-battle-against-air-pollution-4866829

- ↑ The Great Green Wall to Be Built in Africa