France

This article may contain content lifted from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia. You can help by adapting it for Leftypedia by adding more sources or properly attributing the information on this page. (February 2024) |

France, officially the French Republic, is a capitalist country in Western Europe. It had a liberal revolution in 1789 and was established as a republic in 1792, prior to which it was an absolute monarchy. Conflict with other European powers, primarily over fears the liberal revolution would spread, ignited war just a couple months before the proclamation of the republic, with the monarchies of Europe fighting for the preservation of the status quo. Napoleon Bonaparte seized power in 1799 and continued the struggle against the European monarchies, though ultimately lost in 1815. Afterwards, the Bourbon dynasty was reinstalled and monarchism lasted until 1870, when France was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War and its government collapsed, giving rise to the French Third Republic. The modern republic, the French Fifth Republic, was established after the Algiers crisis of 1958.

History

Antiquity

Modern-day France was settled by the Gauls, a Celtic people, starting from the 6th century BC. It was conquered by the Romans from the late-2nd to mid-1st centuries BC, who introduced a full slaveholding mode of production to Gaul, prior to which early class relations only began in its southeast. All of Gaul, and especially the south, was Romanized, with southern Gaul going on to become the first to develop centers of commerce and handicrafts. In the 3rd century Rome had an empire-wide crisis in which commodity production declined, with Gaul's economic ties to Italy weakening and Roman political power declining. Gaul temporarily broke away from Rome though was reconquered in 274, however Germanic tribes seized Gaul as Rome decayed and fell in the 5th century.

Rise of feudalism

The Franks were the most prominent of the Germanic tribes in former Gaul, quickly incorporating all of France by the middle of the 6th century. The subkingdoms of Neustria, Burgundy, and Aquitaine, which roughly comprise modern-day France, practically gained independence in the 7th century, whose Gallo-Roman populations were gradually merged with Franks. The Germanic peoples had abolished slavery and feudal relations developed in their place, which were a synthesis of the Gallo-Roman late classical relations and Frankish communal relations. The Germanic community retained their collective pastures, forests, and wastelands, though the reapportioning of arable land ceased and its ownership became fixed. The rise of private ownership of farmlands led to social stratification of the Germanic people; meanwhile the Gallo-Roman slaves and sharecropping farmers became peasants dependent on landlords, with the harshest form of dependence being serfdom, wherein peasants of low hereditary class were attached to the land like slaves, having minimal rights. By the 9th century a monarchy became entrenched, complete with kings and nobles, with the church also owning large estates. Neustria in northern France underwent the most intense feudalization of the three major French subkingdoms, whereas Burgundy and Aquitaine were still more influenced by the old Roman order. The partition of the Kingdom of the Franks in 843 created West, Middle, and East Francia, with West Francia becoming the first incarnation of France as an independent state.

Kingdom of France

In 987, the secular and ecclesiastical lords elected Hugh Capet as King of the Franks, who began the Capetian dynasty. Around this time the country also began to be called France. Though nominally united, the kingdom was actually divided into numerous virtually independent feudal holdings. The establishment of a solid class society with the feudal lords at the top and dependent peasants at the bottom was completed by the 11th century. From the 11th century onward feudal lords were established as a hereditarily privileged group, with a feudal hierarchy, headed by the king, emerging and being based on vassalage — an oath by vassals to protect their lord's rights. The early Capetian kings were at first limited to northern France, however even there they had to first consolidate power by marriage, inheritance, confiscation, and conquest of their vassals. Southern France was eventually absorbed as well by the 13th century, strengthening the feudal hierarchy from its state of previous disintegration. The growth of cities in the 11th and 12th centuries was accompanied by the replacement of corvee — labor owed to a lord — with in-kind payment. This was in turn replaced with monetary rent in the 13th century. The growth of the market economy in the 13th and 14th centuries allowed many peasants to free themselves from dependence on a lord, mostly by purchasing their way out. Advancements in and expansion of agriculture facilitated a large population, which gave rise to new urban centers as well as the revival of old Roman ones, which became centers of handicrafts and trade. The Crusades of the 12th century established new trading links to the East, helping southern French cities flourish, which also were emancipating themselves from feudal lords around this time through methods such as purchase or armed struggle. Artisan crafts, in particular weaving, reached a high level of excellence. Northern French cities focused more on internal political unity, as they depended on the domestic market. There was a wave of uprisings in the north against feudal lords that were generally supported by kings, who also were engaged in struggle against feudal lords. Only limited self-rule was granted to those cities, which continued to expand throughout the 13th century. Southern cities however were weakened by the Albigensian Crusade and the destruction of the Crusader states in the East, on top of having to face competition from increasingly powerful Italian city-states. Northern France, while consolidating power within the Capetian dynasty, was still struggling against the Plantagenets who ruled England from the mid-12th century. Many lands were wrested from England in the early 13th century and some others were annexed, and by the end of that century southern France became part of the royal domain as well. In this time, Louis IX pursued a centralization policy which made Paris an increasingly important political and economic center of the country. The conduct of numerous wars and the creation of an extensive and comprehensive state apparatus was costly, leading to an all-around increase in taxes — including on church property, which was challenged by Pope Boniface VIII. The French monarchy won out and, with support of the dependent papacy, confiscated church property. In 1302, the king established and convened for the first time the Estates General, which was a legislative and consultative assembly composed of all three estates (or classes). The Estates General helped the king in the struggle against the pope and strengthen the central government.

The Hundred Years' War (1337–1453), fought entirely on French soil, impeded the country's growth. Military operations, resource requisitions, plunder, and high taxes impoverished many regions, diminished the population, and caused a decline in production and trade. The invading English which threatened the very existence of the French state were driven out, retaining only Calais. The French economy gradually recovered in the latter part of the 15th century, with royal power further strengthened. Louis XI expanded French control into Burgundy after a protracted struggle with the powerful dukes there, taking also Picardy and Nivernais. Provence and Brittany were finally incorporated into the royal domain by 1532, essentially completing France's territorial unification. Protective tariffs and other privileges were given to the commercial and artisan elite helped revive handicrafts and trade, with new industries like silk weaving and printing being founded. Established industries also expanded, including metallurgy, metalworking, and the production of cloth and light woolen fabrics. Trade fairs began in Lyon in the later 15th century, which made it one of the most important cities in Europe, with Lyon also displacing Geneva as the banking capital of Europe. Economic ties between various French regions grew stronger and France developed a national market. Linguistic differences however persisted between the north and the south, largely as a consequence of the Hundred Years' War which prevented them from merging, with a single French language evolving in the north whereas the south retained a lot of separate dialects.

Feudal decline and the emergence of capitalism

Capitalist methods transformed French industry and agriculture starting in the late 15th century. Centralized workshops first came about in industries such as shipbuilding, mining, metallurgy, and printing, expanding in the 17th century into artisanal crafts such as mirrors, porcelain, carpets, and tapestries. Artisans and apprentices became skilled workers, and peasants moving to the cities provided unskilled labor. In the 16th century, rich merchants and officials bought up large amounts of land from impoverished peasants and noblemen, then leasing out the land. The more wealthy of the tenants who rented the land had their own tools and livestock, as well as being able to hire laborers. These hired farmers became the main suppliers of grain, cattle, meat and wool to northern French markets in the 17th century. In the south, sharecropping was widely practiced.

Peasants lost their land and wealth from tribute to lords and high taxes, especially during wartime. This gave rise to various peasant movements in the 16th–18th centuries, which the urban masses often joined as well given they were suffering from essentially the same treatment. The monarchy meanwhile became absolute in the 16th century, as it became financially secure and did not really need the Estates General anymore, which convened rarely and for the last time in 1614. The 16th and 17th centuries saw major changes in the composition of the ruling class, for one because the urban bourgeoisie began purchasing judicial and administrative posts that made them nobility, displacing previous knightly nobles (the Nobles of the Sword). These individuals became a new type of nobility called "the Nobles of the Robe", passing their titles to their heirs hereditarily. They supported the monarchy against internal dissent, and furthermore some of them became state creditors — a great asset to the monarchy and its finances. The empowerment of the absolute monarchy meant the feudal aristocracy gradually lost power, particularly after the Italian Wars between 1494 and 1559, where the disbanding of the French Army deprived many noblemen of their military pay.

France experienced a severe social and political crisis in the latter part of the 16th century, a result of resource exhaustion after a series of long and unsuccessful wars as well as the economic effects of the Price Revolution — the doubling of prices from 1500 to 1600, on top of rising taxes. This manifested in a religious conflict between Catholics and Huguenots, a Protestant movement, both of which were feudalist and against absolutism, however their opposition to each other led to a long period of social unrest. France however would enter a period of economic prosperity at the turn of the 17th century, largely due to the mercantilist policy of Henry IV which helped develop manufacture and trade. Around this time France as a nation also began to arise, with the French spoken in the north becoming standard throughout the whole country. Capitalism would go on to dominate industry as well as agriculture in the 18th century, and with this began engaging in conflict with feudal elements as they were restricting its expansion. The bourgeoisie demanded the abolition of the guilds and internal customs barriers, the lowering of export tariffs, the elimination of clerical and nobiliary privileges, and the end of feudal practices in the countryside. Proposals to implement even some of these were blocked by the privileged classes. In the late 1770s a commercial and industrial crisis, coinciding with a famine caused by crop failures, produced a rise in unemployment and exacerbated the suffering of the urban lower clases and the peasantry. During the revolutionary situation that developed in 1788–89, the elections to the Estates General helped to politicize the masses. The deputies of the third estate (the commoners) declared themselves to constitute a national assembly on June 17 and a constituent assembly on July 9.[1]

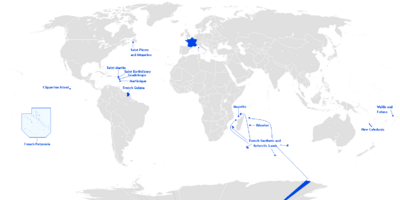

Imperialism

France began its colonization with the Americas in the 16th century, later spreading its empire to all seven continents in the following centuries, and despite losing most of it France still has many colonies throughout the world. During the period of the post-World War II decolonization movements, France attempted to maintain its empire by reforming it into the French Union, which only nominally represented colonies, preserving power within the French Parliament. This lasted from 1946 until 1958, when the French Fifth Republic was established, and which replaced the French Union with the French Community, which was purported to be founded on equality yet still granted France hegemonic status by giving it control of other countries' matters such as foreign affairs, defense, currency, economic policies, and control of raw materials. This lasted until 1995 and was characterized by a lack of engagement from African leaders.[2]

Presently, the French government seeks to deflect, minimize, and engage in projection as it regards imperialism — often with extreme irony. In a 2022 visit to Africa for example, President Macron condemned Russia as "one of the last imperial colonial powers" — saying this in countries where France has a long past of brutal repressions and a continuing presence of exploitation.[3] Speaking about Russia again later that year, Macron stated the invasion of Ukraine harked back to an "age of imperialism and colonies", and that "France refuses this and will work persistently for peace".[4] All the while, the French government resists even apologizing for its colonial atrocities, let alone paying reparations, at most giving vague "commemorations".[5] This attitude pervades across administrations, with François Hollande for example refusing to pay reparations to Haiti for his country's role in the slave trade, stating that "What has been, has been",[6] and Macron saying that it would be "totally ridiculous" for France to "pay a subsidy, or recognise, or compensate" for colonialism.[7]

Historical

Haiti

Haiti won its independence from France following a slave revolt in 1804, to which France responded by navally blockading the country and extracting massive compensation for its property losses. In 2013 money, €21 billion was paid to France from 1825 to 1946, helping to cripple Haiti's finances and contributing to its legacy of underdevelopment that left it as one of the poorest countries in the world. French President François Hollande announced no reparations would be paid to Haiti for France's role in the slave trade, establishing a cruel irony of the colonial subject being the only one to make such payments.[6]

Interventions

Libya, during the First Libyan Civil War of 2011

A series of protests that began in 2009 escalated into a civil war when NATO, led by France and the United Kingdom, backed Anti–Gaddafi forces and launched bombing raids against the Gaddafi government. France and other imperialist countries had long been looking to get rid of Gaddafi as he was a stabilizing force for the Middle East and Africa, seeking to unite and empower it with a strong, single currency, an endogenous telecommunications system, and other such.[8] France flew 35% of NATO's airstrikes against Libya, the highest amount of any country. Obama later called out French President Nicolas Sarkozy, along with British Prime Minister David Cameron, as partly to blame for the "mess" they created, thinking that the proximity of Libya to Europe would have caused European powers such as these to be more invested in the outcome (the refugee crisis followed soon afterward).[9]

Support for Hissène Habré of Chad

Habré was the former President of Chad from 1982 until his deposition in 1990. He was brought to power with support from France and the United States, which provided training, arms, and financing.[10] France supported him as he was a reliable Francophone leader who was also at odds with Libya, backing him and fighting off an insurgency backed by Libya and later Libya itself, after which Chad was used to station troops indefinitely for France. Habré became one of Africa's bloodiest rulers, being convicted of multiple crimes against humanity in 2016 by an international tribunal, including rape, sexual slavery, and the killing of 40,000 people.[11]

Support for Mobutu Sese Soko of Zaire (modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo)

Mobutu got the French to believe that rebels in Zaire's Katanga province were communist, and France intervened from 1977 to 1978 thinking that it was stopping the spread of communism. In reality the French were duped into helping Mobutu repress insurgents in the south of the country and retain an iron grip over it, with Mobutu going on to plunder Zaire for the next two decades.[12]

Rwanda during the Rwandan Civil War

In 1990, the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front invaded Rwanda (a French-speaking country) from Uganda (an English-speaking country), as the result of years of discrimination and violence against Tutsis. France considered this to be an attack on the Francophone world, and seeking to protect its legitimacy within the sphere of such, came to the support of Rwanda. The Rwandan government fell eventually and the RPF was victorious nonetheless, however France's efforts prolonged the war and the genocide in the last phase of it.[12]

Modern age

[W]ithout Africa, France will have no history in the 21st century.

— Francois Mitterrand, French president 1981–1995, Politique Française et Abandon, 1957

Today France still exerts a lot of power over its former African colonies through its sphere of influence known as Françafrique, which is used for the extraction of resources such as uranium, gold, natural gas, iron, and diamonds, besides other wealth. Despite former French President François Hollande proclaiming the end of Françafrique in 2012[13] and the beginning of a new age of equality, French domination over its former African colonies persists in economic, military, and cultural matters — echoing both the rhetoric and reality of the French Community. Part of this is composed of currency controls[14] as manifested through the CFA Franc currency, divided into West and Central variants. Eight African countries use the West African CFA Franc, which is pegged to the Euro and the use of which stipulates keeping at least 50% of the country's currency reserves in the French Treasury, binding West African nations to France and possibly reducing intra-regional trade, on top of making countries dependent on exporting their limited goods. There is also the Central African CFA Franc which is likewise used to siphon resources to France.[15] From the beginning this monetary union revealed its exploitative nature, with Guinea holding a referendum in 1958 on whether to join it, and upon 95% of the population voting against the measure France immediately pulled out 4,000 civil servants, judges, teachers, doctors, and technicians, instructing them to sabotage everything they left behind, with books burned, buildings demolished, agricultural tools destroyed, and an assortment of other vindictive behavior that served to punish the disobedient neocolony.[16] The proposed currency Eco was set to replace the West African CFA Franc in 2020, which would remove the demand of keeping at least half of currency reserves in France on top of having France withdraw from all governing bodies of the Central Bank of West African States,[17] yet was delayed for three to five years by the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the currency, once implemented, may end up centering on Nigeria and its heavily oil-based economy — ultimately setting the new currency largely in the hands of oil-controlling nations.[18] This situation however does indicate a loss of power by France in the region to rising states like China and Nigeria, and as expressed for example by Marine Le Pen, a politician who has become increasingly popular in recent years, and through which part of the French bourgeoisie expresses its intents, the current model of managing Françafrique is becoming too expensive; a development in line with historic imperialist tendencies to make their colonial relations less direct as management costs go up.[16] France will certainly seek to preserve its exploitative grasp on Africa however the details as to how this will be under the Eco are unclear, with even the infrastructure for such a currency being still lacking.

France stations troops in its former African colonies, which it has used in over thirty interventions since the end of the colonial period,[19] among these various instances of supporting French-backed dictators who often got rich off of French foreign aid, which was ostensibly to help the local populace.

French will be the number one language in Africa and maybe even the world if we play our cards right in the coming decades.

— French President Emmanuel Macron, 2017 announcement to students in Burkina Faso[20]

France currently is trying to promote the African language abroad, particularly in Africa. This serves to integrate more economic activity into the French-dominated Françafrique, banking on the fact that former French colonies have among the highest fertility rates in the world and thus represent areas with a potential for a high level of growth.[21]

As a neocolonial power, as before in the age of a more physical empire, France is interested in inciting a certain level of sectarianism in its client states to ensure that they remain dependent on their overlord, as they thus become incapable of developing or maintaining security independently. Third World lands that have never developed themselves as a nation are ripe for such a policy; among these, countries such as Iraq and Syria, where France established a military presence in 2015 and armed groups like the YPG and PKK under the pretext of fighting the Islamic State. These groups are further supported by French military bases and over twenty NGOs, with some members of the YPG and PKK even being hosted at the Élysée Palace by President Macron.[22] Support for these two in particular works to undermine a rival power — Turkey, as the Kurds are in conflict with it,[23] besides destabilizing and ripping apart at the territory of Iraq and Syria[24] — possibly even undermining other countries with Kurds such as Iran, another country that France is overwhelmingly antagonistic towards.[25] This is in line with the policy of inciting racial, religious and ideological division among subjugated populations in France's older colonial times, were countrymen ended up turning against one another and even ended up fighting on behalf of their colonizer.[22]

Other atrocities

On July 10, 1985, French agents in diving gear planted a bomb on the hull of Rainbow Warrior, the flagship vessel of Greenpeace which was preparing for a protest voyage to a French nuclear test site in the South Pacific. The explosion sunk the ship in Auckland harbor in New Zealand, killing Dutch photographer Fernando Pereira. French authorities denied responsibility two days later even as New Zealand police arrested two French secret service agents in Auckland. Pressured by New Zealand authorities, the French government launched an investigation which concluded after several weeks that the French agents were merely spying on Greenpeace. Later that year however a British newspaper uncovered evidence of French President Francois Mitterrand's authorization of the bombing, leading to several top-level resignations in Mitterrand's cabinet and an admission by French Prime Minister Laurent Fabius that the agents were ordered to sink the vessel. The two agents were sentence to 10 years in prison by New Zealand but were released the following year after negotiations with France.[26]

References

- ↑ France. (n.d.) The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition. (1970-1979). Retrieved May 16, 2021 from https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/France

- ↑ Henry Grimal, La décolonisation de 1919 à nos jours, Armand Colin, 1965. Éditions Complexe (revised and updated edition, 1985), p. 335

- ↑ Macron calls Russia 'one of the last imperial colonial powers' on Africa visit. France 24.

- ↑ Russian invasion of Ukraine a return to 'age of imperialism', Macron tells UN. France 24.

- ↑ France won’t apologize for Algeria colonization. Politico.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 France refuses to pay slavery reparations. The Local.

- ↑ Macron rules out reparations for colonialism. Radio France Internationale.

- ↑ Africa Enjoys Unlimited Telecommunication Services Thanks To Gaddafi. The African Exponent.

- ↑ Obama blasts Cameron, Sarkozy for Libya ‘mess’. France 24.

- ↑ Chad's Torture Victims Pursue Habre in Court. The Washington Post.

- ↑ Hissene Habre: Chad's ex-ruler convicted of crimes against humanity. BBC.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 The flawed logic behind French military interventions in Africa. The Conversation.

- ↑ Hollande hails ‘new chapter’ between France and Africa. France 24.

- ↑ Nzaou-Kongo, Aubin (2020). "International Law and Monetary Sovereignty. The Current Problems of the International Mastery of the CFA Franc and the Crisis of Sovereign Equality". Social Science Research Network.

- ↑ African protests over the CFA 'colonial currency'. BBC.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 The “French Colonial Tax”: A misleading heuristic for understanding Françafrique. The Africa Report.

- ↑ France is set to end the use of the 75-year-old controversial CFA franc in West Africa. CNN.

- ↑ West Africa’s new currency could now be delayed by five years. CNBC.

- ↑ France in the Sahel: a case of the reluctant multilateralist?. The Conversation.

- ↑ Macron’s global ambitions for the French language will fail. Financial Times.

- ↑ Macron launches drive to boost French language around world. The Guardian.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Times and people change, but France’s colonial aims do not. Daily Sabah.

- ↑ Turkey Slams France's Offer of Mediation Over Syrian Kurd Militia. Voice of America.

- ↑ France's Macron vows support for northern Syrians, Kurdish militia. Reuters.

- ↑ Views of Europe Slide Sharply in Global Poll, While Views of China Improve. BBC World Service. p. 29

- ↑ https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-sinking-of-the-rainbow-warrior. History.