Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Leftypedia's quality standards. |

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. |

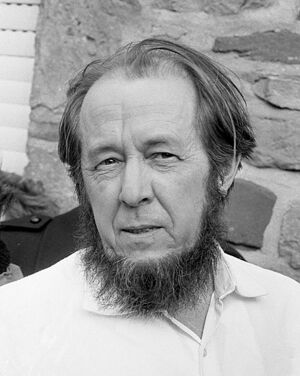

Alexander Solzhenitsyn (SOHL-zhə-NEET-sin; December 11, 1918, Kislovodsk, Tersk region, RSFSR — August 3, 2008, Moscow, Russia) was an anti-Semitic Russian novelist and political dissident who lived and worked in the USSR, Switzerland, USA and the Russian Federation. An outspoken critic of the USSR and communism, he is best known for writing The Gulag Archipelago.

The Gulag Archipelago

The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation is a three-volume book written between 1958 and 1968.

Reliability and bias

Though the book is widely believed to be a rather reliable and authoritative account of the Gulag system by the uninformed, it is in fact has little credibility. Solzhenitsyn's own wife, Natalia, admitted that the book's contents are nothing more than mere folklore based on unreliable information, and that she was "perplexed" that the West had accepted The Gulag Archipelago as "the solemn, ultimate truth", saying its significance had been "overestimated and wrongly appraised". Pointing out that the book's subtitle is "An Experiment in Literary Investigation", she said that her husband did not regard the work as either historical or scientific research.[1][2]

Khrushchev encouraged people like Solzhenitsyn to write books describing Stalin negatively. Solzhenitsyn was only allowed to publish his book in the Soviet Union also because had yet to come out as an anti-socialist and blatant reactionary.[citation needed] His other book, The Life of Ivan Denisovich, was seen by Khrushchev as helping to accelerate de-Stalinization even though it went a good deal further than other "thaw" literature. As Khrushchev privately put it, "If it had been written with less talent it would perhaps have been an erroneous thing [to publish it], but in its present form it has got to be beneficial."[3] Mikhail Suslov and other Politburo members had opposed its publication. After Khrushchev was deposed, Solzhenitsyn fell out with the party, after which he was kicked out of the country.

The reason why Solzhenitsyn was sent to the Gulag in the first place was for two reasons: making derogatory remarks about the conduct of the war by Stalin, and planning an officers' coup.[citation needed] Even then, he was treated rather well during his time there, receiving successful medical treatment after he developed pancreatic cancer.[4] His semi-autobiographical retelling of his treatment, Cancer Ward, describes the actual conditions in the camp as being similar to those of an ordinary prison[citation needed] — a far cry from the descriptions of Gulag Archipelago.

Views

Anti-Semitism

Solzhenitsyn was accused of anti-Semitism by Jewish and non-Jewish scholars alike starting in the early 1970s[5] and throughout his lifetime. However, obituaries at the time of his death denied or downplayed the evidence,[a] and his public credibility as an author remains largely untainted. Many who cite The Gulag Archipelago deny the charge of anti-Semitism against Solzhenitsyn or are simply ignorant of the facts.

Solzhenitsyn remained an anti-Semite until the end of his life. In 2003, after twelve years of work,[6] he published his authorial last gasp, Two Hundred Years Together, a pseudo-historical[7] retelling of Russian history as a "dualistic struggle, fought between us [Russians] and them [Jews].... a zero-sum game, where the success of one – usually the Jews – can only come at the expense of the other."[8] The work persistently attempts to portray Russian leftism, in particular the Bolshevik movement, as a product of Jewish meddling[9] and voices support for Tsarist anti-Jewish policies.[10] Solzhenitsyn goes on to endorse claims that Jews played a role in sabotaging Russia during both world wars,[11] that Jewish tavernkeepers were responsible for promoting alcoholism in the Pale of Settlement,[10] and that the Jews themselves, on account of "subversive" activities and "lack of respect" for the Gentiles, were ultimately to blame for Russian pogroms.[12] He also curates a list of prominent Bolsheviks with Jewish surnames but, in his fervor, includes several non-Jews, and even some Russians, in his list.[13]

There were many attempts to defend the central author of the anti-communist canon. Yevgeny Satanovsky, president of the Russian Jewish Congress, defended the book as "a mistake, but even geniuses make mistakes.... Richard Wagner did not like the Jews, but was a great composer." He admitted, however, that in terms of historical fact "it is so bad as to be beyond criticism."[14] Several of the most prominent anti-communist authors also provided various defenses. Richard Pipes treated Solzhenitsyn's anti-Semitism as obvious but unproblematic, writing that although Solzhenitsyn "unquestionably [believed] the [Russian] Revolution.... was the doing of Jews", "every culture has its own brand of anti-Semitism" and Solzhenitsyn's was not racist but merely "religious and cultural".[5] Robert Conquest, however, rejected any charge of anti-Semitism as "ludicrous" and even suggested that the accusation reflected anti-Slavic stereotypes.[5] Robert Service simply refused to apologize for Solzhenitsyn's work, calling it "absolutely right".[14] Anti-communist and Zionist author Elie Wiesel cited no evidence in his defense of Solzhenitsyn, merely stating that the author was guilty only of "unconscious" bias and "too intelligent, too honest, too courageous" to be an anti-Semite.[5] Israeli professor Mikhail Agursky put his defense bluntly: "If you support Israel the way Solzhenitsyn does today, you are not an anti-Semite."[5] Perhaps the most sterling credential cited in the author's support was an "extreme [Russian] nationalist" publication which called Solzhenitsyn "a traitor who sold himself to world Jewry."[15]

Anti-communism

Solzhenitsyn subscribed to the Judeo-Bolshevism theory, which purported that the Jews were ultimately responsible for the Russian Revolution.[5][9]

Reactionism

According to Arthur Schlesinger Jr. in Solzhenitsyn at Harvard:

Solzhenitsyn has no belief in what he called at Harvard "the way of western pluralistic democracy." People lived for centuries without democracy, he wrote in 1973, "and were not always worse off." Russia under authoritarian rule [i.e., Tsarism] "did not experience episodes of self-destruction like those of the 20th century, and for 10 centuries millions of our peasant forebears died feeling that their lives had not been too unbearable."[16]

Roy Medvedev, no friend of the CPSU, noted that Solzhenitsyn "proposed founding an authoritarian, theocratic state in the USSR and transferring the whole Russian population to uninhabited territories in northeast Siberia, there to begin a new life without cities, big industries, railroads, automobiles, and democracy." He was a reactionary in a literal sense, condemning the modern world. He also argued that the US lost the Vietnam War because it did not try hard enough.[citation needed][needs copy edit] As far as The Gulag Archipelago goes, there are a number of articles that argue against it presenting the typical experience, one of which is Was the Gulag an Archipelago? De-Convoyed Prisoners and Porous Borders in the Camps of Western Siberia.[citation needed]

Notes

- ↑ Just for instance:

- "Solzhenitsyn, chronicler of Russia under communism, dies at 89," LA Times: "His image as the conscience of Communist-ruled Russia dimmed after his repatriation and his diatribes on the denigration of his nation that were at times tainted with paranoia, anti-Semitism and bigotry."

- "Obituary: Alexander Solzhenitsyn", BBC News: "In 2000, his book, Two Hundred Years Together, again covered sensitive ground in exploring the position of Jews in Soviet society. He denied some charges of anti-Semitism."

- "Alexander Solzhenitsyn, A 'Man With A Mission'", NPR News: "Some saw in it hints of anti-Semitism from the author, a Slavophile and extoller of village life in Orthodox Christian Russia."

Other articles from the time, including in The Guardian and the New York Times, do not even contain such hints of controversy as these.

References

- ↑ Natalya Reshetovskaya, 84, Is Dead; Solzhenitsyn's Wife Questioned 'Gulag', NY Times, June 6, 2003.

- ↑ Solzhenitsyn's Ex‐Wife Says ‘Gulag’ Is ‘Folklore’, NY Times, Feb. 6, 1974.

- ↑ One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich: A Critical Companion, edited by Alexis Klimoff, page 99.

- ↑ Cancer Ward by the editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Solzhenitsyn and Anti-Semitism: A New Debate. The New York Times.

- ↑ Polouektova, Ksenia (2008). "Alexander Solzhenitsyn's 200 Years Together and the 'Russian Question'" (PDF). Analysis of current trends in antisemitism (31). For the author's credentials, see "Ksenia Polouektova-Krimer" at Opendemocracy.net. This work is frequently cited here because no official English translation of Two Hundred Years Together exists as of 2023. Unofficial translations can be found online, such as this one at Archive.org.

- ↑ Polouektova 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ John Klier, "No Prize for History," History Today (Nov. 2002): 60. As cited in Polouektova, 2008.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Polouektova 2008, p. 12.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Polouektova 2008, p. 9.

- ↑ Polouektova 2008, p. 15.

- ↑ Polouektova 2008, p. 10.

- ↑ Polouektova 2008, p. 11-12.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Solzhenitsyn breaks last taboo of the revolution. The Guardian.

- ↑ Russian Jews accuse Solzhenitsyn of altering history. Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur, Jr. (1980). Template:Citation/make link. In Berman, Ronald. Template:Citation/make link. Ethics and Public Policy Center, Washington, D.C.. Template:Citation/identifier. Schlesinger, Arthur, Jr. (1980). "The Solzhenitsyn We Refuse to See". In Berman, Ronald (ed.). Solzhenitsyn at Harvard. Ethics and Public Policy Center, Washington, D.C. p. 66. ISBN 0896330230. (It's on Libgen.)