German Democratic Republic

The German Democratic Republic (GDR or DDR (from the German "Deutsche Demokratische Republic")), unofficially known as East Germany, was a state in central Europe that existed from 7 October 1949 to 3 October 1990, oriented towards Marxism–Leninism until 1989. In that year, it underwent the "Peaceful Revolution", where its borders with the west where opened, the Socialist Unity Party fell from power, and a parliamentary democracy was instituted which led to the reunification of Germany the following year.

The GDR had a higher rate of economic growth than West Germany, even though they were previously of same country. This is in spite of the GDR being stripped of much of its industry and agriculture in Prussia and Silesia, forcing it to reindustrialize to a large extent. With this, West Germany had many advantages over East Germany such as access to the Ruhrgebiet, where a large part of the German industry was located, on top of having access to imperialist funding and wealth. In fact, West German itself became an imperialist power, largely in Africa, wherein it established “free trade agreements” with investor protection clauses that effectively limited the ability of African countries to implement policies that would impede the gains of foreign investors. The GDR on the other hand did not conduct any imperialism and had no access to the export market of the Western world and the Asian capitalist powers, which were the backbone of West German industry during the “economic miracle”.

| German Democratic Republic Deutsche Demokratische Republik | |

|---|---|

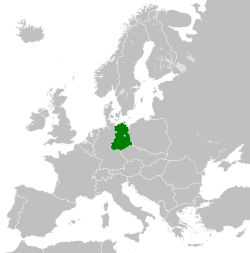

[[File: |300px|center|frameless]] |300px|center|frameless]]Map of GDR

| |

[[File: |125x63px|frameless]] |125x63px|frameless]]

|

[[File: |85x88px|frameless]] |85x88px|frameless]]

|

| Flag | State Emblem |

History

World War II left Germany a shadow of its former self. Cities had been leveled, and the economy had been utterly devastated. Eastern Germany in particular was at a serious disadvantage; it had always been far less industrialized than Western Germany, and as such, it had depended largely upon the West for its economic needs.

Before World War II, the area that later became East Germany was not well developed industrially. Because this area lacked raw materials, heavy industry was generally located in other parts of the German state. Compounding the problems for the newly created East German state in 1949 was the massive destruction during World War II of the industrial plant that had existed there and the subsequent Soviet dismantling and removal of factories and equipment that had survived the war. [...] During the interwar years, the territory that is now East Germany was profoundly dependent on external economic ties. In the mid-1930s, it shipped almost half of its total production to the other parts of Germany. […] This domestic trade featured sales of agricultural products; textiles; products of light industry, such as cameras, typewriters, and optical equipment; and purchases of industrial goods and equipment.

— US Federal Research Division, [1]

Thus, Eastern Germany depended totally on the West for its heavy industrial needs, and paid for these needs by selling its agricultural and light industrial products. However, this balance between East and West was thrown off after the war:

Major dislocations occurred after World War II, when Germany was divided into two sections, one part dominated by the Soviet Union, and the other by the Western Allies. Because it could no longer rely on its former system of internal and external trading, the Soviet Zone of Occupation had to be restructured and made more self-sufficient through the construction of basic industry.

— US Federal Research Division, [2]

This was challenging for the young GDR, especially seeing as it received virtually no large-scale economic aid from the USSR (which was too busy reconstructing itself after WWII to worry about funding the GDR). In addition, the GDR had to pay heavy reparations to the USSR for the damage caused during WWII. This acted as a major obstacle to development. According to The East German Economy, 1945–2010, published by the German Historical Institute, direct and indirect reparations paid by East Germany between 1946 and 1953 amounted to $14 billion in 1938 prices.

The reorientation and restructuring of the East German economy would have been difficult in any case. The substantial reparations costs that the Soviet Union imposed on its occupied zone, and later on East Germany, made the process even more difficult. Payments continued into the early 1950s, ending only with the death of Stalin. According to Western estimates, these payments amounted to about 25 percent of total East German production through 1953.

— US Federal Research Division, [3]

This is in direct contrast to the West, which received large aid investments from the United States as part of the Marshall Plan, as well as lucrative trade relationships with the developed nations. After the war on the second of August, 1945 the allies presented the Postdam agreement which described the demilitarization of Germany, repayments that Germany needed to pay and the control of allied powers.[1] While the agreement was supposed to cause allies to control Germany jointly their differing economic and political goals made it impossible. By the start of 1950s, two German states existed: the market capitalist Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), and the socialist planned German Democratic Republic (GDR). The war losses USSR had during the war amounted to 1,700 cities and urban areas, 70,000 villages, 32,000 enterprises and 65 kilometers of railway, thousands of schools and hospitals and about 20 million people lost their home. The 30% of national wealth was lost. The numbers were released by Izvestia, a government run newspaper and were thought of by Western powers as made up for propaganda purposes. The numbers released after the fall of USSR show that was not the case.[2] The Soviet zone was divided economically into two parts, the north which was predominantly agricultural, and the south which was heavily industrialized, being the Third Reich industrial core. The south focused on metal working, electrical, chemical and machine tools. Despite that the Soviet zone had problems with lack of raw materials like copper. Iron and hard coal. At the other hand the quantity of brown coal, potash, gravel and uranium which was to become important in Soviet nuclear industry were plentiful, with the GDR becoming the third largest uranium producer in the world.[3] Overall the German industry did not suffer great losses in the war with 15% lost in industrial capacity.[4]

The Berlin Wall was built in 1961, for a variety of reasons. For one it was to stop West Germany from siphoning citizens away using material incentives, especially through West Berlin which was heavily subsidized in order to appeal to East Germans.[5] The wall was also built to prevent currency manipulation, as in both Germanys, marks, though officially separated into eastern and western varieties, operated at the same exchange rate. However, in West Berlin, eastern marks could be bought at a discount, which resulted in many East Germans employed in West Berlin, who received their pay in the western Deutsche Marks, to exchange their Deutsche Marks into eastern marks at the favorable West Berlin exchange rate, then bringing their inflated salaries back to East Berlin where they would buy massive quantities of East German goods at government-controlled low prices. These cheap goods would then be brought into West Berlin where they were sold for Deutsche Marks, effectively transferring the wealth of East Germany to one's own self. Simple workers could and have become millionaires within a few months of this. On top of this, the status of Berlin was in dispute — the Berlin Wall indicated that the Soviets were unlikely to invade West Berlin, in a move that eased tensions and brought relief to the capitalist powers. JFK himself remarked that "a wall is a hell of a lot better than a war".[6]

In 1989, the PRC offered to save the GDR from collapse:

Comrade Egon Krenz

Today I held extensive talks with comrade Lin Hanxiong, minister of urban planning (who first visited the GDR in 1982 to revitalise relations). Comrade Lin Hanxiong stated that the fate of socialism in the GDR is of utmost strategic importance for world socialism and for the victory of socialism in the PRC. The CPC leadership is ready to do whatever is necessary to support the survival of socialism in the GDR. In light of complicated labour shortages in the GDR, the PRC is willing to offer any required amount of skilled labour in any necessary qualification.

The PRC does not expect any payment in foreign exchange, because they consider it political assistance. Balance settlement could be done by goods.

Comrade Lin Hanxiong announced his willingness to travel to Berlin on short notice to engage in direct talks with the responsible state organs. The PRC is ready for very short term decisions. Comrade Lin Hanxiong stressed that ideally a reply by the GDR should arrive before the 5th congress of the CC CPC at the beginning of November.

Request answer.

berthold

27.10. 14.00

Aftermath

Most people in the West imagine the fall of the GDR as a time of widespread euphoria and freedom; however, for millions of people in the GDR this was far from the case. One account of this time was written for the Guardian by Bruni de la Motte, an East German woman who has since become a British trade union negotiator. She reports that widespread unemployment and misery occurred after the short twentieth century:

Little is known here [the West] about what happened to the GDR economy when the wall fell. Once the border was open the government decided to set up a trusteeship to ensure that “publicly owned enterprises” (the majority of businesses) would be transferred to the citizens who’d created the wealth. However, a few months before unification, the then newly elected conservative government handed over the trusteeship to west German appointees, many representing big business interests. The idea of “publicly owned” assets being transferred to citizens was quietly dropped. Instead all assets were privatized at breakneck speed. More then 85% were bought by West Germans and many were closed soon after. In the countryside 1.7 million hectares of agricultural and forest land were sold off and 80% of agricultural workers lost their job.

— Bruni de la Motte, [4]

Another article from the Guardian reports on the long-term impact this has had on the economy in Eastern Germany, noting that there has been virtually no advancement in the East-to-West productivity ratio since 1991:

Productivity in the former east was 70% of that in the west in 1991 and rose to just 73% in 2012, in part a legacy of the number of factories that were bought by West German industrialists and deliberately run into the ground to scotch competition. […] Experts say the fact that most of the large industry and production bases are in the west and that those in the east are far smaller — with most employers in agriculture or service industries like meat-processing and call centres — will have a long-term effect of increasingly holding back the economy in the east and ensuring that the wage discrepancy remains and likely worsens.

— Kate Connolly, [5]

A mass-purging of academia and professional life likewise took place after the short twentieth century:

Large numbers of ordinary workers lost their jobs, but so too did thousands of research workers and academics. As a result of the purging of academia, research and scientific establishments in a process of political vetting, more than a million individuals with degrees lost their jobs. This constituted about 50% of that group, creating in East Germany the highest percentage of professional unemployment in the world; all university chancellors and directors of state enterprises as well as 75,000 teachers lost their jobs and many were blacklisted. This process was in stark contrast to what happened in West Germany after the war, when few ex-Nazis were treated in this manner.

— Bruni de la Motte, [6]

This coincided with a housing crisis as well as the mass seizure of workers’ homes:

In the GDR everyone had a legally guaranteed security of tenure and ownership to the properties where they lived. After unification, 2.2m claims by non-GDR citizens were made on their homes. Many lost houses they’d lived in for decades; a number committed suicide rather than give them up. Ironically, claims for restitution the other way around, by East Germans on properties in the West, were rejected as “out of time”.

— Bruni de la Motte, [7]

She remarks that since the short twentieth century, many people have come to appreciate the benefits that the socialists offered:

Since the demise of the GDR, many have come to recognize and regret that the genuine “social achievements” they enjoyed were dismantled: social and gender equality, full employment and lack of existential fears, as well as subsidized rents, public transport, culture and sports facilities. Unfortunately, the collapse of the GDR and “state socialism” came shortly before the collapse of the “free market” system in the west.

— Bruni de la Motte, [8]

This is supported by the fact that (as mentioned above) 57% of former East Germans say that life was better in the planned economy.[7][8] Bruni de la Motte explains this thus:

The GDR experience of socialism stands in marked contrast to the dismantling of the welfare state and the concomitant rampant privatization of every aspect of life now taking place in Western Europe, from culture to healthcare and other essential services, as well as to the denial of social values and the extreme individualization of life. We live in an atomized society, rapidly falling apart, with little social ethos and no long-term goals. Many today, especially young people, are living without hope or sense of a secure future. Socialism can still offer an antidote and an alternative. And the experience of socialist countries like the GDR can provide pointers for a way forward and help renew one’s hope.

— Bruni de la Motte, [9]

Politics

The leading party, the SED, would discuss with the other parties in the coalition what candidates should run at all levels of government, and how many members of a party there would be for each municipality. Though the SED was given a hegemonic role in government, the other parties did provide input of their own. There was a certain level of disenfranchisement with elections however, as some suspected the results to be predetermined.

Surveillance

While the GDR did indeed have a large internal security apparatus, considering the backdrop of a much larger and richer FRG constantly trying to subvert them and take them over, it is perhaps understandable. In 1987 there was 91,000 secret policemen, a significant amount but what is often done disingenuously is to attribute all of the GDR's internal security forces and employees as members or secret agents of the Stasi, which they were not. There was 15,646 regular police, 6226 police liaisons with neighborhood watch groups, 8294 criminal police, 6212 traffic police, 31,555 National Guard troops (11,000 of which are included in regular secret policeman numbers), 8526 prison guards and 3337 immigration officers (not including the additional 10,000 of the 91,000 secret police figure also directly involved in emigration affairs). It should be noted that fewer ordinary police were needed in the GDR because the socialist system attacked the underlying causes of crime instead of merely punishing offenders. In 1988, for example, there was 7 acts of crime committed in the GDR per 1000 residents to 71 acts of crime per thousand residents in the FRG. It should also be noted that most of the secret police's work in the GDR were security checks on those who wanted to visit the FRG and most of their arrests were concerned with those attempting to illegally migrate to the west. The total number of people who had given information to the Stasi at some point in the organizations existence for whatever reason was roughly 600,000, though only 174,000 were listed as informants by the Stasi in 1989. The 174,000 figure is mostly made up of communist party members who would cooperate with the Stasi if needed, generally providing information such as worker morale, the mood of the public regarding the general economic and political situation etc and were rarely if ever contacted. Only 2% of Stasi personnel (about 4000 people) were involved in spying and surveillance of suspected dissidents. Only 430 agents were utilized in the infamous telephone or room bugging with most of this work being used against foreign embassies and missions, contrary to what Stasiland and The Lives of Others might portray. Most Stasi informants were paid nothing and simply acted out of a sense of responsibility of office (i.e. being an official in the SED or having an important job with its accompanying social expectations) or patriotism and a desire to cooperate with the authorities. The suggestion that the Stasi would lie about their documents for their own internal use to somehow play down their numbers or their prolifacy is simply unfounded and lacks merit.

Berlin Wall

Main Article: Berlin Wall

Economy

The GDR did not have a united 5-year plan like the Soviet Union, but instead there were several plans running in different parts of the country at different times. From 1963 however there was begun the New Economic System introduced by Ulbricht, similar to the Liberman reforms in the USSR during the same decade in that it tried to give managers more responsibility and rewards for high-quality output and reduction of wastage. East German enterprises were also grouped into associations known as VVBs, which were designed to make planning more rational. The New Economic System was scrapped in 1970 in favor of more centralized control, partly because it had been rather disappointing and partly because the Soviets discouraged talk of economic reform in the Warsaw Pact for a few years after the intervention in Czechoslovakia. The East Germans tried to develop VVBs, however in the end had a system that was pretty similar to the Soviet model, and as a result had similar problems.

Despite all of its significant disadvantages, the GDR’s economy managed to overcome its difficulties and develop at an unusually rapid rate. This is especially true in terms of heavy industry:

During the 1950s, East Germany made significant economic progress, at least as indicated by the gross figures. By 1960 investment had grown by a factor of about 4.5, while gross industrial production had increased by a factor of about 2.9. Within that broad category of industrial production, the basic sectors, such as machinery and transport equipment, grew especially rapidly, while the consumer sectors such as textiles lagged behind.

— US Federal Research Division, [10]

Despite the priority given to heavy industry, consumption also increased steadily during this period:

Consumption grew significantly in the first years, although from a very low base, and showed respectable growth rates over the entire decade.

— US Federal Research Division, [11]

From 1949 to the late 1960s the consumption of meat, dairy, eggs, fish, sugar, tea, and alcohol all increased.[9]

At the end of the 1950s, some analysts feared an economic crisis in the East, spurred by the ‘brain drain’ from East to West; however, this did not occur, and the GDR’s economy continued to grow impressively in the 1960s.

As the 1950s ended, pessimism about the future seemed rather appropriate. Surprisingly, however, after the construction of the Berlin Wall and several years of consolidation and realignment, East Germany entered a period of impressive economic growth that produced clear benefits for the people. For the years 1966–1970, GDP and national income grew at average annual rates of 6.3 and 5.2 percent, respectively. Simultaneously, investment grew at an average annual rate of 10.7 percent, retail trade at 4.6 percent, and real per capita income at 4.2 percent.

— US Federal Research Division, [12]

This growth continued on through the next decade:

As of 1970, growth rates in the various sectors of the economy did not differ greatly from those of a decade earlier. […] Production reached about 140 to 150 percent of the levels of a decade earlier. […] The growth rates in production resulted in substantial increases in personal consumption. [T]hroughout the 1970s the East German economy as a whole enjoyed relatively strong and stable growth. In 1971, First Secretary Honecker declared the “raising of the material and cultural living standard” of the population to be a “principal task” of the economy; private consumption grew at an average annual rate of 4.8 percent from 1971 to 1975 and 4.0 percent from 1976 to 1980. […] The 1976–1980 Five Year Plan achieved an average annual growth rate of 4.1 percent.

— US Federal Research Division, [13]

The 1980s saw some economic difficulties for the GDR as Western banks clamped down on credit for the East and the USSR reduced oil deliveries by ten percent. This led to a period of slow growth as the GDR rushed to step up exports; despite this, the economy did manage to pull through and deliver impressive growth results during this period (though it did fall short of the plan).

The 1981–1985 plan period proved to be a difficult time for the East German economy. […] However, by the end of the period the economy had chalked up a respectable overall performance, with an average annual growth rate of 4.5 percent (the plan target had been 5.1 percent).

— US Federal Research Division, [14]

The overall impacts of the industrialization strategy of the GDR were extremely positive.

Industry is the dominant sector of the East German economy, and is the principal basis for the relatively high standard of living. East Germany ranks among the world's top industrial nations, and in the Comecon it ranks second only to the Soviet Union.

— US Federal Research Division, [15]

Infrastructure

The East German standard of living has improved greatly since 1949 [when the GDR was established]. Most observers, both East and West, agree that in the 1980s East Germans enjoyed the highest standard of living in Eastern Europe. Major improvements occurred, especially after 1971, when the Honecker regime announced its commitment to fulfilling the “principal task” of the economy, which was defined as the enhancement of the material and cultural well-being of all citizens.

— US Federal Research Division, [16]

This focus on increasing quality of life for all citizens, rather than providing profit for the capitalist class, is a unique feature of the planned economy, which provided steadily improving living standards:

Since the inception of the regime, the monthly earned income of the average East German has increased steadily in terms of effective purchasing power. According to the 1986 East German statistical yearbook, the average monthly income for workers in the socialized sector of the economy increased from 311 GDR marks in 1950 to 555 GDR marks in 1960, 755 GDR marks in 1970, and 1,130 GDR marks in 1985. Because most consumer prices had been stable during this time, the 1985 figure represented a better-than-threefold increase over the past thirty-five years.

— US Federal Research Division, [17]

State subsidies meant that basic necessities (food, housing, and so forth), public services (healthcare, education, etc.), and even small luxuries (restaurant meals, concerts, etc.) were all remarkably cheap, especially when compared to the capitalist West:

In East Germany, the GDR mark can purchase a great number of basic necessities because the state subsidies their production and distribution to the people. Thus housing, which consumes a considerable portion of the earnings of an average family in the West, constituted less than 3 percent of the expenditures of a typical worker family in 1984. Milk, potatoes, bread, and public transportation were also relatively cheap. Many services, such as medical care and education, continued to be available without cost to all but a very few. Even restaurant meals, concerts, and postage stamps were inexpensive by Western standards. […] In the mid-1980s, East Germans had no difficulty obtaining meat, butter, potatoes, bread, clothing, and most other essentials.

— US Federal Research Division, [18]

The GDR also greatly improved the housing situation:

Beginning in the 1960s, the government initiated a major campaign to provide modern housing facilities; it sought to eliminate the longstanding housing shortage, and modernize fully the existing stock by 1990. By the early 1980s, the program had provided nearly 2 million new or renovated units, and 2 million more were to be added by 1990. As of 1985, progress in this area appeared to be satisfactory, and plan targets were being met or exceeded.

— US Federal Research Division, [19]

The situation in terms of consumer goods was also improving; the US Federal Research Division reports that as of 1985 in the GDR, 99 percent of households had a refrigerator, 92 percent had a washing machine, and 93 percent had a television. These numbers are compatible to the United States in 2016 (though washing machine ownership was higher, and TV ownership slightly lower, in the GDR). Economists had often thought that the GDR mark was weaker in terms of purchasing power than the West German D-mark; however, a study from the Institute for Economic Research in West Berlin (as reported by the US Federal Research Division) disproved this idea:

In 1983, the Institute for Economic Research in West Berlin undertook one of its periodic studies in which the purchasing power of the GDR mark was measured against that of the West German D-mark. […] The Institute concluded that, as a whole, the GDR mark should be considered to have 106 percent of the value of the D-mark in purchasing power, an impressive gain over the 76 percent estimated for 1960, 86 percent for 1969, and 100 percent for 1977. [T]he analysis clearly invalidated the view commonly held in the West that the GDR mark had very little purchasing power.

— US Federal Research Division, [20]

Health

The GDR provided medical treatment free of charge to its people. This system allowed them to keep up with West Germany in terms of healthcare conditions, despite the latter being wealthier (by virtue of its extensive trade relations with developed nations). The Health Care Financing Review (a US government-affiliated publication) reports:

In terms of real resources devoted to health services and in terms of health service activities, the two countries seem to have been fairly similar. The GDR was reported as having 2.3 physicians per thousand in 1985 (World Health Organization, 1987), compared with 2.6 in the FRG. In 1977, the GDR was reported as having 10.6 hospital beds per thousand, compared with 11.8 in the FRG, and both countries had similar levels of dentists and pharmacists per thousand. Hospital length of stay was reported as similar in the two countries, Given that hospital beds per thousand were similar, this suggests that admission rates were not very different. Finally, consultation rates with doctors seem to have been similar in the two countries at 9.0 per person in the GDR in 1976 and 10.9 per person in the FRG in 1975 (Health OECD: Facts and Trends, forthcoming). If the GDR enjoyed a similar volume of health services to the FRG but had much lower health expenditures per capita, then the prices of health services must have been much lower in the GDR.

— Health Care Financing Review, [21]

The GDR maintained high healthcare standards, which improved steadily, and in some cases faster than those in the West (though starting at a lower level; Eastern Germany had always been worse-off in terms of health than the West):

Turning to health status, in 1987, the reported expectation of life at birth in eastern Germany, 69.9 years for males and 76.0 for females, was not far behind that of western Germany at 72.2 for males and 78.9 for females. The infant mortality rate, which had been 7.2 per 100 in 1950, had fallen to 0.92 in 1986. Although the infant mortality rate was above that of western Germany in 1986 (0.85), the fall since 1950 had been larger. If the official figures can be believed, the former GDR had respectable health statistics for a country with its standard of living. […] Improvements to health status in eastern Germany seem to have kept up, more or less, with those in western Germany.

— Health Care Financing Review, [22]

Life expectancy in the German Democratic Republic was higher than that in Austria, Australia, Belgium, the British Empire, Canada, Italy, Switzerland, and West Germany.[10]

Education

Attendance at kindergarten was not mandatory, but the majority of children from ages three to six attended. The state considered kindergartens an important element of the overall educational program. The schools focused on health and physical fitness, development of socialist values, and the teaching of rudimentary skills. The regime has experimented with combined schools of childcare centers and kindergartens, which introduce the child gradually into a more regimented program of activities and ease the pains of adjustment. In 1985 there were 13,148 preschools providing care for 788,095 children (about 91 percent of children eligible to attend).

— US Federal Research Division, [23]

After this, children entered the compulsory stage of education:

Compulsory education began at the age of six, when every child entered the ten-grade, coeducational general poly-technical school. The program was divided into three sections. The primary stage included grades one through three, where children were taught the basic skills of reading, writing, and mathematics. The primary stage also introduced children to the fundamentals of good citizenship and, in accordance with the 1965 education law, provided them with their “first knowledge and understanding of nature, work, and socialist society.” Instruction emphasized German language, literature, and art as a means of developing the child's expressive and linguistic skills; about 60 percent of classroom time was devoted to this component. Mathematics instruction accounted for about 24 percent of the curriculum and included an introduction to fundamental mathematical laws and relations. Another 8 percent was devoted to physical education, which comprised exercises, games, and activities designed to develop coordination and physical skill. Poly-technical instruction was also begun at the primary level and consisted of gardening and crafts that gave the child a basic appreciation of technology, the economy, and the worker; about 8 percent of classroom time was allotted to such instruction.

— US Federal Research Division, [24]

After completing mandatory education, students had several choices:

Upon completion of the compulsory ten-year education, the student had essentially three options. The most frequently chosen option was to begin a two-year period of vocational training. In 1985 about 86 percent of those who had completed their ten-year course of study began some kind of vocational training. During vocational training, the student became an apprentice, usually at a local or state enterprise. Students received eighteen months of training in selected vocations and specialized in the final six months. In 1985 approximately 6 percent of those who had completed their poly-technical education entered a three-year program of vocational training. This program led to the Abitur, or end-of-school examination. Passing the Abitur enabled the student to apply to a technical institute or university, although this route to higher education was considered very difficult. In 1985 East Germany had a total of 963 vocational schools; 719 were connected with industries, and another 244 were municipal vocational schools. Vocational schools served 377,567 students.

— US Federal Research Division, [25]

Students were guaranteed a job upon completing the ten-year compulsory education:

The educational system’s major goal was producing technically qualified personnel to fill the manpower needs of the economy. The government guaranteed employment to those who completed the mandatory ten-year program.

— US Federal Research Division, [26]

The university system was also of remarkably high-quality, and attendance was extremely inexpensive (though entrance requirements were very competitive):

In 1985 East Germany had 54 universities and colleges, with a total enrollment of 129,628 students. Women made up about 50 percent of the student population. Courses in engineering and technology headed the list of popular subjects. Medicine, economics, and education were also popular choices. There were 239 technical institutions, with a total student population of 162,221. About 61 percent of the students studied full time, while the remainder enrolled in correspondence study or took evening classes. The three most popular fields of study at the institutes were medicine and health, engineering and technology, and economics. Courses at the university and technical institutes consisted primarily of lectures and examinations. Completion of the program led to a diploma or license, depending on the field of study. As of the mid-1980s, higher education was very inexpensive, and many of the textbooks were provided free of charge. Full or partial financial assistance in the form of scholarships was available for most students, and living expenses were generally minimal because most students continued to live at home during their courses of study. Germans have a high regard for education, and the regime has generally supported young people who have wanted to upgrade their level of skills through further training or education.

— US Federal Research Division, [27]

Culture

Inexpensive cultural activities such as theaters and concerts were widely available.[11]

Gender relations

The East German record in the area of women’s rights has been good. Women have been well-represented in the work force, comprising about half of the economically active population. As of 1984, approx. 80 percent of women of working age (between eighteen and sixty) were employed. The state has encouraged women to seek work and pursue careers and has provided aid to working mothers in the form of day-care centers generous maternity benefits.

— US Federal Research Division, [28]

Women’s access to education was very strong in the GDR, again much stronger than in the capitalist West:

The state also has made a concerted effort to provide educational opportunities for women. The number of women with a university or technical school education has increased over the years. Of the students enrolled in universities and colleges in 1985, about 50 percent were women.

— US Federal Research Division, [29]

Birth control was widely-available and free of cost, and abortion was available upon the bearer’s request:

A liberal abortion law, promulgated in 1972 amid protests from religious circles, permits abortion upon request of the mother. […] As of the mid 1980s, information on contraceptive methods was available to the public, and women could obtain birth control pills at no cost.

— US Federal Research Division, [30]

In addition, the GDR sought to provide assistance to working mothers through a highly-developed child-care system:

An elaborate network of daycare centers provides care for the child while the mother is at work. In 1984 there were 6,605 year-round nurseries with room for 296,653 children. These nurseries provided care for 63 percent of eligible children.

— US Federal Research Division, [31]

Cuisine

The German Democratic Republic had their own foods, such as Spreewald pickles, Mocha Fix, Schnittchen, and Schnitzel, among others.

References

- ↑ Potsdam Agreement

- ↑ Figures from Dimitri Wolkogonow, Stalin. Triumpf und Tragödie. Ein politisches Porträt (Düsseldorf, 1993), 681–2; Rainer Karlsch and Jochen Laufer, eds., Sowjetische Demontagen in Deutschland 1944– 1949 (Berlin, 2002), 31–2; Uhl, Teilung, 7–9. On the validity of the figures, see the more recent publications Jochen Laufer, Pax Sovietica. Stalin, die Westmächte und die deutsche Frage 1941–1945 (Cologne, 2009), 263; Bogdan Musial, Stalins Beutezug. Die Plünderung Deutschlands und der Aufstieg der Sowjetunion zur Weltmacht (Berlin, 2010), 249, 452.

- ↑ Rainer Karlsch, Uran für Moskau. Die Wismut – Eine populäre Geschichte (Berlin, 2007), 231–7; Matthias Judt, ed., DDR-Geschichte in Dokumenten (Berlin, 1997), 89–91; Karlsch, Allein bezahlt?, 35; Steiner, Von Plan zu Plan, 19–24.

- ↑ Wolfgang Zank, Wirtschaft und Arbeit in Ostdeutschland

- ↑ Tobias Hochscherf, Christoph Laucht, Andrew Plowman, Divided, But Not Disconnected: German Experiences of the Cold War, p. 109, Berghahn Books, 2013, ISBN 9781782381006

- ↑ Berlin Wall. History.

- ↑ de la Motte, Bruni; Green, John (2009). Template:Citation/make link. Artery Publications. Template:Citation/identifier. https://archive.org/stream/StasiHellOrWorkersParadise.

de la Motte, Bruni; Green, John (2009). Stasi Hell or Workers' Paradise? Socialism in the GDR: What Can We Learn From It?. Artery Publications. ISBN 9978-0-9558228-3-4.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ↑ https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/homesick-for-a-dictatorship-majority-of-eastern-germans-feel-life-better-under-communism-a-634122.html

- ↑ Turgeon, Lynn (1972). Template:Citation/make link. Monthly Review Press. p. xv. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7iUwYR74MlbcFBxbWxsdHNLMHM. Turgeon, Lynn (1972). Transitional Economic Systems, The Polish-Czech Example. Monthly Review Press. p. xv.

- ↑ The Health Crisis in the USSR: An Exchange. The New York Review.

- ↑ de la Motte, Bruni; Green, John (2009). Template:Citation/make link. Artery Publications. pp. 29–30. Template:Citation/identifier. https://archive.org/stream/StasiHellOrWorkersParadise.

de la Motte, Bruni; Green, John (2009). Stasi Hell or Workers' Paradise? Socialism in the GDR: What Can We Learn From It?. Artery Publications. pp. 29–30. ISBN 9978-0-9558228-3-4.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help)